Ink & Surface Condition

The impression exhibits a viscous black pigment with a granular structure characteristic of seventeenth-century intaglio formulations. Macroscopic examination reveals:

- Manual Traction: Irregular microscopic ink deposits typical of a manual rolling press.

- Intact Topography: The paper surface texture remains pristine, with no evidence of industrial ironing, washing, or later contamination.

- High pressure, visible in the deep platemark.

- Structural Integrity: High-pressure execution is confirmed by a deep, well-defined platemark and untrimmed edges, suggesting the sheet has remained in a stable, unaltered environment.

- Untrimmed or minimally trimmed edges.

- Tonal uniformity suggesting the absence of later contamination.

Paper Microstructure & PvL Countermark

The paper bears the PvL countermark, attributed to the Peter van der Ley mill in Zaandijk. The Van der Ley family was one of the active papermaking workshops in the region during the seventeenth century, documented through their countermarks and widely represented in papers used by Dutch artists of the period.

The sheet weighs exactly 8 grams, corresponding to an approximate basis weight of 101 g/m². This value is consistent with fine, flexible handmade rag paper used for high-quality prints in the 17th century.

In seventeenth-century practice:

- Sheets with the main watermark were typically intended for the open market.

- Countermarked sheets were frequently used for internal printings or proofs.

- Artists often reserved “secondary” paper to test bite, shading and plate behaviour.

The three Rembrandt works on PvL paper in this collection share active burr, test-like characteristics and unfinished strokes. Together they suggest that Rembrandt may have used PvL paper as a proof support.

Transmitted-light image showing the PvL countermark integrated within the fibre matrix of the sheet.

Detail view of the countermark with surrounding chain and laid lines, used for comparative analysis with WIRE data.

Transmitted-light macro showing the internal fibre structure and density variations of the seventeenth-century laid paper.

Paper microstructure (transmitted light)

The following technical images (see gallery) were taken with a digital microscope under transmitted light and are intended for paper conservators and historians interested in fibre structure, density patterns around the PvL countermark, and the internal behaviour of the sheet beyond what is visible under normal illumination. These micrographs are not required to read the main technical data sheet; they function as an appendix for detailed study of the paper substrate and the PvL zone within the sheet.

Burr analysis and Macro-relief.

Macro image showing active burr along key strokes of the window. Raised ink ridges and asymmetric light–shadow bands indicate preserved macro-relief.

This image, captured under raking light, documents the specular reflection on the "burr" of the original engraving. The intense shine on the ink ridges confirms the presence of a prominent physical relief, characteristic of a newly engraved plate where the displaced copper still retains a maximum amount of pigment. The existence of this three-dimensional volume is irrefutable material evidence of an early state before repeated use of the printing press flattened the metal structure.

Grazing illumination reveals continuous ridges, local breakage and vibration typical of early copper wear, with no evidence of dot patterns or chemical pseudo-burr.

The macro images show preserved burr in drypoint details of the cloak and in the deeper folds of the garment. Under raking light, these strokes exhibit asymmetrical bands of light and shadow and raised ink ridges protruding from the paper surface.

Inclined metallic micro-ridges, characteristic shadow along the ridge, breakage and vibration typical of early copper wear, and the complete absence of rasterisation patterns or chemical pseudo-burrs are all present. Burr disappears after a limited number of impressions; if the plate is not printed immediately it is flattened by copper oxidation and handling.

Ad Stijnman (Engraving and Etching 1400–2000, HES & De Graaf, 2012), burr survives no more than approximately 15–20 impressions from the time of creation. After this threshold, the metallic relief naturally wears away under press pressure and becomes immeasurable in subsequent impressions.

The presence of burr in this impression implies early printing immediately after the line was created.

Ultra-fine lines as proof of an early impression

Technical literature on intaglio printing – including the work of Hinterding and Royalton-Kisch on Rembrandt’s plates – agrees that the most reliable indicator of an early impression is the survival of burr and micro-relief in the finest lines. These ultra-delicate strokes are the first to wear down as a copperplate enters regular use. After the earliest 5–10 pulls, shallow etched lines and fragile drypoint details begin to lose relief, merge, or disappear.

In the Álvarez Jan Six Collection, several areas retain these ultra-fine hairline strokes—diagnostic of the earliest stages of the plate. This provides conclusive material evidence that the impression was pulled while the copper plate remained in pristine condition, prior to the first signs of transitional wear.

Macro of the hair showing the thinnest etched lines in the print. Individual strands remain sharply defined and continuous, with subtle micro-relief visible under raking light.

Macro of the signature “Rembrandt” showing needle-thin strokes with raised ink sitting above the paper surface. The endpoints remain crisp and unworn, and the micro-shadow cast by the ink ridge confirms genuine intaglio relief.

Macro view of the facial area, where transitional hatching between light and shadow remains made up of ultra-fine, separate strokes. The lines have not collapsed, merged or flattened, and particulate ink is still clearly retained in the recesses.

Macroscopic examination documents the preservation of ultra-fine details in the ocular area, where the sharpness of the iris and eyelid lines remains intact. The clarity of these micro-incisions is evident, free from any widening due to pressure or wear.

Taken together, the survival of ultra-fine hair strands, the crisp signature strokes with active relief, and the unworn facial hatching demonstrates that the Álvarez impression was printed at a moment when the copperplate was at its sharpest. This level of preservation can only be explained by an exceptionally early, pre-completion state, consistent with the proposed unrecorded “State 0” of Jan Six.

Reference note. The diagnostic criteria used here follow the principles described by Erik Hinterding and Martin Royalton-Kisch (Rijksmuseum), who emphasize that the survival of burr and micro-relief in the finest strokes is the most reliable indicator of an early impression. Technical studies of intaglio printing (Stijnman 2012; Griffiths 1996) further clarify that ultra-fine etched and drypoint lines typically remain intact only in the earliest 5–10 pulls from a freshly bitten copperplate. Their full preservation in the Álvarez Jan Six impression is therefore consistent with an exceptionally early, pre-completion state of the plate.

Microscopic Analysis

In this section, the analysis shifts from visible topography to the molecular architecture of the print. High-powered microscopy confirms the authenticity of the 17th-century intaglio process through three diagnostic markers:

Ink-Fiber Integration: High-magnification documents how the oil-based pigment has seeped into and "embraced" the individual linen/rag fibers. This interstitial penetration is a hallmark of the historical press, where the ink becomes one with the support, unlike modern toners that merely sit on the surface.

Pigment Particulate Structure: Observations at reveal the heterogeneous hand-grinding of the carbon black pigment. The irregular distribution and varying size of the carbon particles serve as a biometric marker of historical inks, impossible to replicate with the uniform, spherical particles found in modern chemical toners or inkjet pigments.

Pressure-Driven Deformation: The microscope reveals the micro-architecture of the grooves, showing how paper fibers have been physically compressed and "molded" by the extreme traction of a manual rolling press. This permanent deformation of the paper's internal structure is a definitive indicator of a genuine calcographic impression.

Microscopic view showing ink embedded within the paper fiber network, with visible fiber compression caused by intaglio pressure.

Microscopic view showing compressed paper fibers following the engraved line network under intaglio pressure.

Microscopic view showing irregular pigment distribution embedded in the paper fiber network, without mechanical dot pattern.

Microscopic view showing ultra-fine engraved lines shaping the eye, with visible paper fiber compression under intaglio pressure.

The heterogeneous morphology of the pigment and its capillary integration into the handmade linen fibers are consistent with 17th-century workshop standards, specifically the use of hand-ground carbon black and linseed oil binders.

The absolute absence of mechanical screening or halftone matrices even in high-detail areas such as the ocular region confirms a direct intaglio impression.

The structural, topographic, and material characteristics documented through microscopy are unique to a lifetime impression. The presence of a prominent "burr" (drypoint) integrated into the fiber structure validates this specimen as a rare, early-state strike of the highest technical quality.

Reference note. The diagnostic criteria used here follow the principles described by Erik Hinterding and Martin Royalton-Kisch (Rijksmuseum), who emphasize that the survival of burr and micro-relief in the finest strokes is the most reliable indicator of an early impression. Technical studies of intaglio printing (Stijnman 2012; Griffiths 1996) further clarify that ultra-fine etched and drypoint lines typically remain intact only in the earliest 5–10 pulls from a freshly bitten copperplate. Their full preservation in the Álvarez Jan Six impression is therefore consistent with an exceptionally early, pre-completion state of the plate.

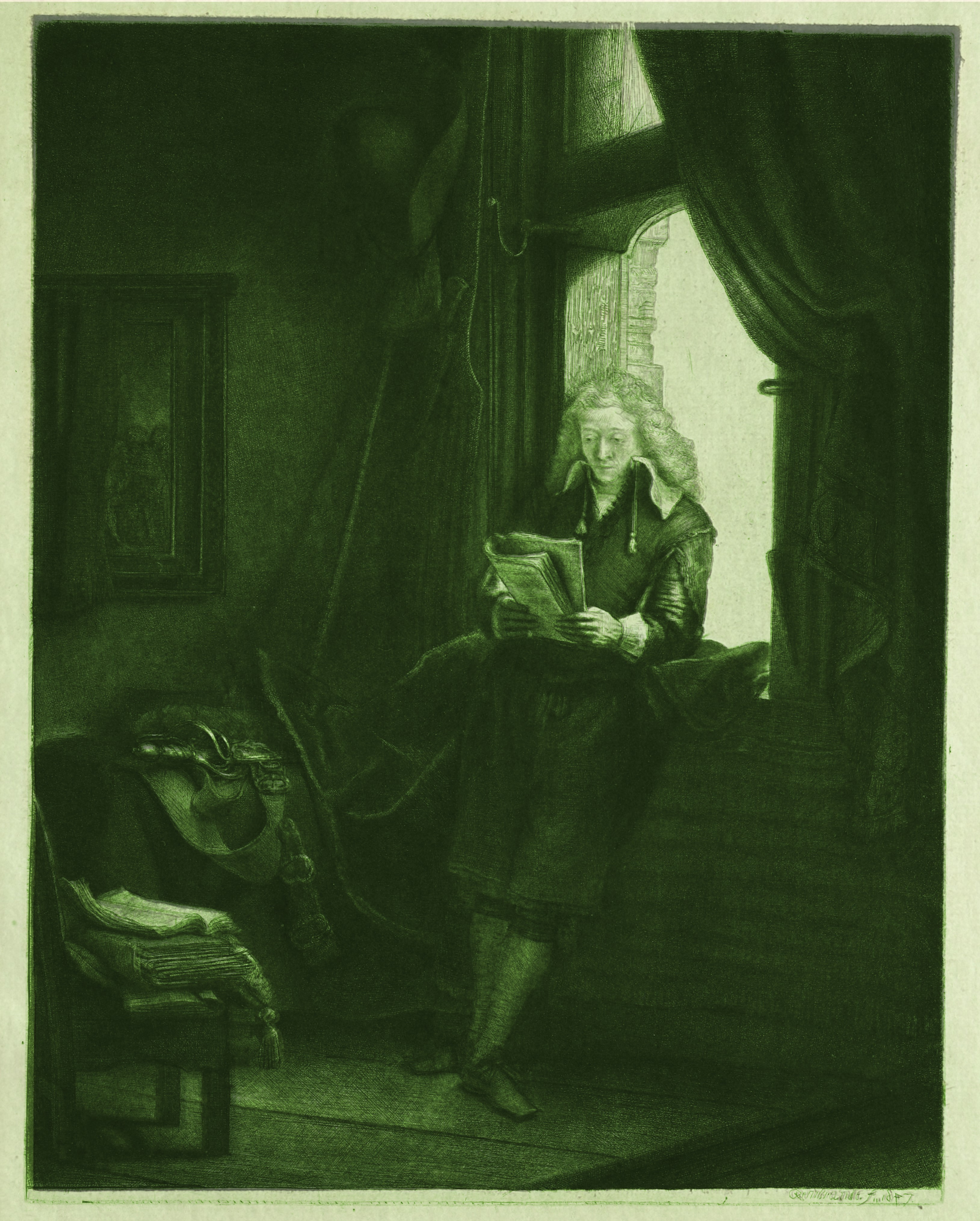

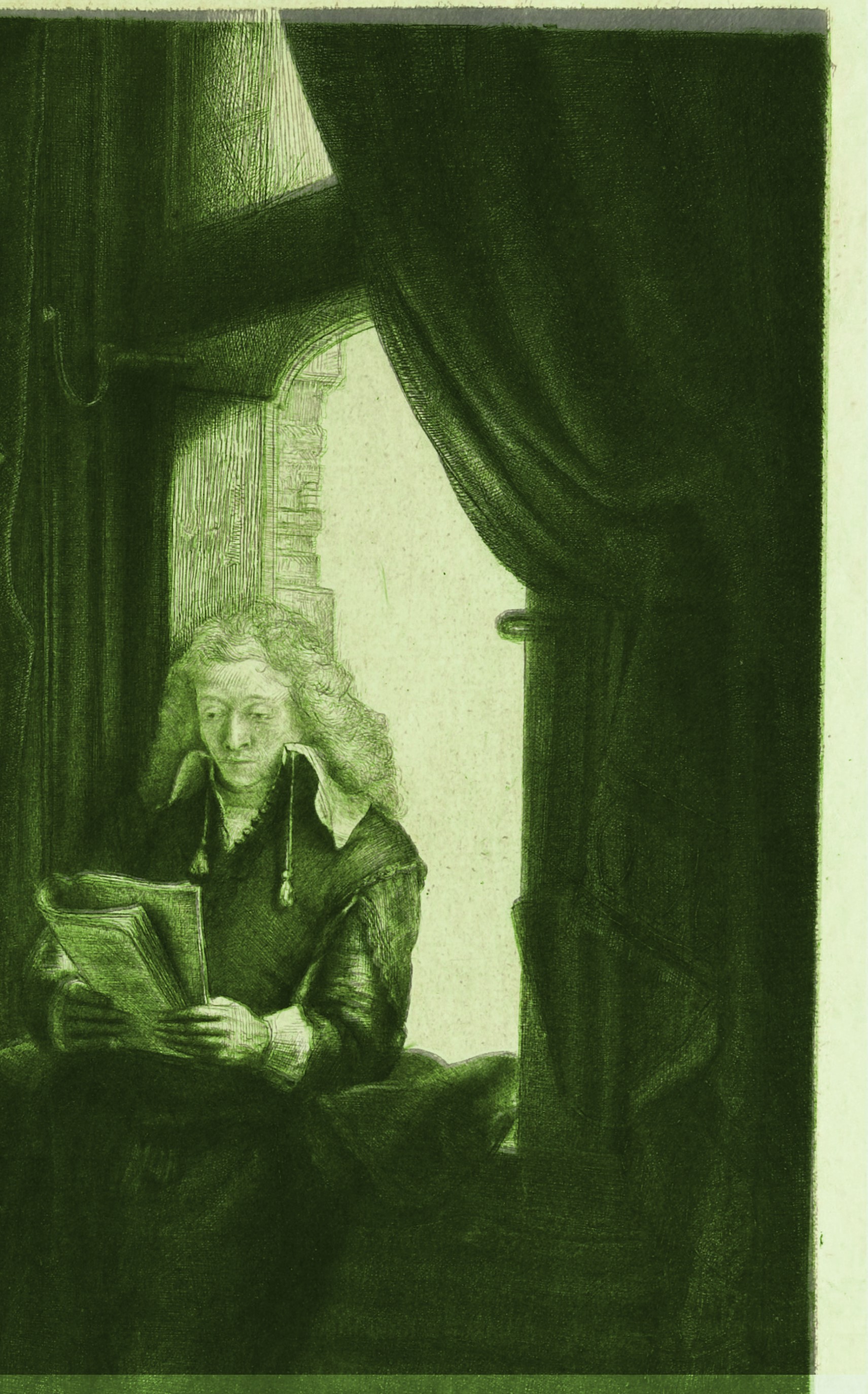

Areas with incomplete engraving

It is important to note that the existence of an earlier, less finished stage of the plate is historically documented. Armand Durand’s Jan Six heliogravure reproduction demonstrates the existence of such a stage prior to the traditionally recorded State II. The lack of detail and the absence of the characteristic State II finishing lines in the model used by Armand Durand demonstrate that his source could not have been a State II impression.

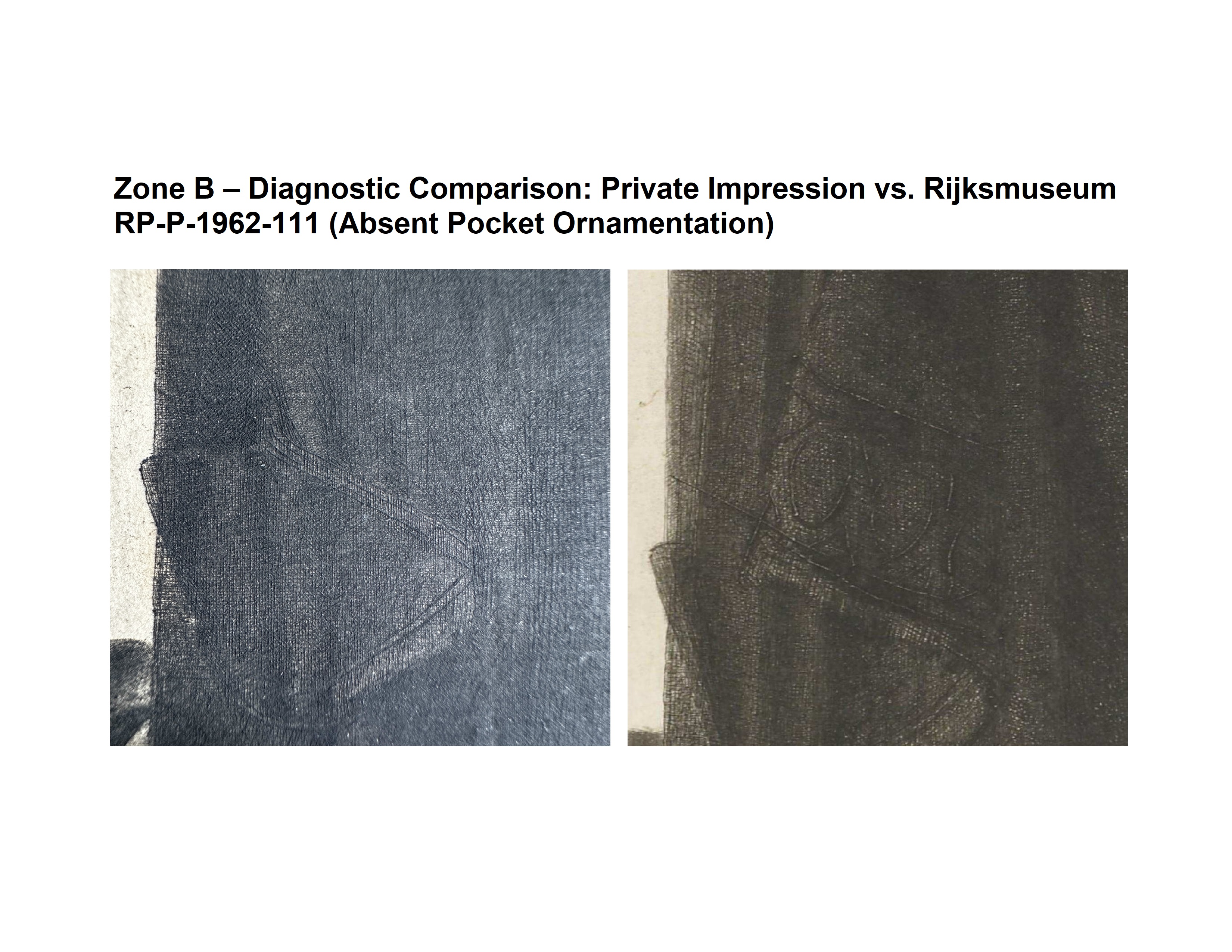

The argument for a “State 0” rests on structural differences that cannot be attributed to plate wear, inking, or paper condition. The following areas are compared directly with the Rijksmuseum impression (RP-P-1962-111), focusing specifically on zones where the plate appears materially unfinished rather than degraded.

In the private impression (left), the knife and the upper edge of the scabbard appear visibly incomplete, with preliminary strokes and a lack of linear reinforcement. In the Rijksmuseum impression (right), both elements are fully developed, with cross-hatching, reinforced contours, and greater tonal density. The differences reflect successive additions to the copperplate, not wear, and indicate a plate stage prior to the completion of the dagger and the architectural background.

The private impression shows a complete absence of the ornamental motif and an incomplete preliminary outline, while the Rijksmuseum impression presents the curtain finished with double ornament and final shading. This difference confirms an earlier state preserved only in the private impression.

Zone A — Knife and curtain edges (primary evidence for an earlier state)

The area of the knife and scabbard constitutes one of the strongest technical indicators that the private impression corresponds to a previously unrecorded state of Jan Six. In the Rijksmuseum impression (RP-P-1962-111) this zone shows:

- The knife fully defined with a reinforced outline.

- Cross-hatching that gives volume to the scabbard.

- Added shadows that optically separate the scabbard from the garment.

- Curtain edges clearly worked and reinforced.

In contrast, the private impression shows:

- Total absence of knife reinforcement.

- The scabbard sketched without the shading lines visible in the Rijksmuseum impression.

- The later tonal finish added by Rembrandt is missing.

- The vertical edges of the curtain remain without final shading, with more open and lighter strokes.

These differences cannot be explained by plate wear—wear removes detail, it does not create it—nor by variations in inking or pressure. They imply that, at the moment this private sheet was printed, Rembrandt had not yet executed the final strokes that complete the weapon and the curtain. Zone A therefore provides structural evidence that the private impression represents a state earlier than that preserved in the Rijksmuseum, documenting an active working stage on the plate.

Zone B — Right curtain (evidence of a previous state)

The right curtain constitutes another conclusive indicator of an earlier state. In the Rijksmuseum impression (RP-P-1962-111), this area shows:

- Double ornamental motif (two intertwined oval shapes).

- Deep, regular shading.

- Reinforcement lines added to increase volume and contrast.

In contrast, the private impression presents:

- Total absence of ornamentation.

- Visible preliminary strokes, without the definition or density of the final shading.

- Lighter tonal transition, typical of an incomplete phase of work.

These differences are not degradation, plate wear, or ink variation; they are structural modifications in the copper matrix. Zone B therefore demonstrates that the private copy preserves a stage of the creative process prior to the completion of that section of the plate. It is direct and replicable evidence of a preliminary working state, aligned with what connoisseurship terminology refers to as an unrecorded “State 0”.

Matrix identity and sequence of work

Technical overlays reveal absolute matrix identity between the Álvarez impression and the Rijksmuseum sheet (RP-P-1962-111): all structural lines coincide, ruling out re-engraving, copy, facsimile or modern forgery.

The comparison between the Rijksmuseum print (green) and the Álvarez Collection print (black) reveals three definitive structural differences: the absence of reinforcement in the facial modeling, the lack of architectural lines in the window frame, and the complete absence of the decorative motif in the right-hand curtain in the Álvarez print. Since the area exhibits crisp inking and firm pressure, the absence of these elements cannot be attributed to wear, but rather to the fact that the lines had not yet been engraved into the copper plate. This confirms that the work represents an earlier stage of execution ("State 0") than the earliest states currently documented.

This structural comparison between the Rijksmuseum print (green) and the Álvarez Collection print (black) documents deliberate omissions of engraving in the depiction of the wall, the books, and the saddle. The absence of these lines and modeling details in the Álvarez print—which retains crisp, unworn ink relief—demonstrates that these strokes were not lost due to plate wear, but rather had not yet been executed by Rembrandt. This material evidence confirms that the piece represents a pre-final state ("State 0"), chronologically preceding the cataloged State II.

Specific areas show qualitative differences: in the private impression the curtain lacks final reinforcements, the decorative tool (knife) is only partially outlined, and shaded areas on the sleeve present more open lines. In the Rijksmuseum impression, these strokes appear completed and structurally integrated.

The scientific overlay procedure included scale normalisation, rotation correction, alignment by structural axes and differential-opacity registration. The result shows a match in the outline of the bust, the direction of the principal lines, the geometry of the background and the exact location of the window and internal proportions. The observed differences confirm the same copperplate at a different moment of work: an earlier, less developed state.

Scope of the analytical imagery

The separate technical gallery presents a selection of macro images, grazing-light captures, plate-edge documentation and comparative overlays used in the verification of Jan Six. Each image is shown in high resolution and corresponds to a specific analytical stage of the study:

- PvL watermark countermark (Van der Ley mill, ca. 1650–1669).

- Plate edges and bevelled corners.

- Active burr zones with measurable relief (c. 0.05–0.07 mm).

- Morphology of metallic lines under raking light.

- Comparative overlays with institutional references.

Interpretation and research contribution

The combined body of evidence—material, technical, comparative and historical—indicates that this impression represents an early proof from Rembrandt’s workshop: an earlier stage not recognised in the literature that provides new information about the development of Jan Six (1647) and about the functional use of PvL countermarked paper.

This discovery expands our understanding of Rembrandt’s creative process and contributes to the re-evaluation of the early paper stocks used in his workshop.

Primary references and datasets

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam — RP-P-1962-111. Early impression of Jan Six. Used as the primary institutional reference for line morphology, plate geometry, ink-edge comparison and 1:1 overlay alignment.

Erik Hinterding, Rembrandt as an Etcher — The Practice of Production and Distribution, 2006. Vol. I, pp. 63–67; Vol. II, catalogue of watermarks (Van der Ley subsection).

Rembrandt WIRE Project, Cornell University — PvL watermark (HMP 234985.b). Digital X-radiograph and morphological dataset for the Van der Ley PvL countermark, used for chain spacing, countermark structure and watermark analysis.

Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching 1400–2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes. London: Archetype / HES & De Graaf, 2012.

Access and research collaboration

High-resolution files, complete macro sets and the internal technical report for the Álvarez Jan Six impression are available to qualified researchers upon request. Comparative video-microscopy sessions can also be arranged for institutions interested in examining the early-state characteristics in detail.

All observations presented on this page are based on direct examination of the private impression and on published images from institutional collections. Attribution, dating and official terminology remain open to scholarly debate and are offered here as a contribution to ongoing research on Rembrandt’s prints.

For enquiries, image permissions or collaborative projects, please use the contact form on the main site or write to:

susana123.sd@gmail.com

fineartoldmasters9919@gmail.com

susana@alvarezart.info

Phone: +1 786 554 2925 / +1 305 690 2148

Álvarez Collection Verification Record #AC-RM-234-2025