Burr is one of the most fragile microstructures produced by a copper plate: it begins to diminish after only a small number of impressions and continues to degrade even during storage due to oxidation and micro-relief collapse (Stijnman 2012, p. 145). The localized persistence observed here suggests an early printing phase and optimal inking/pressure conditions capable of preserving micro-relief.

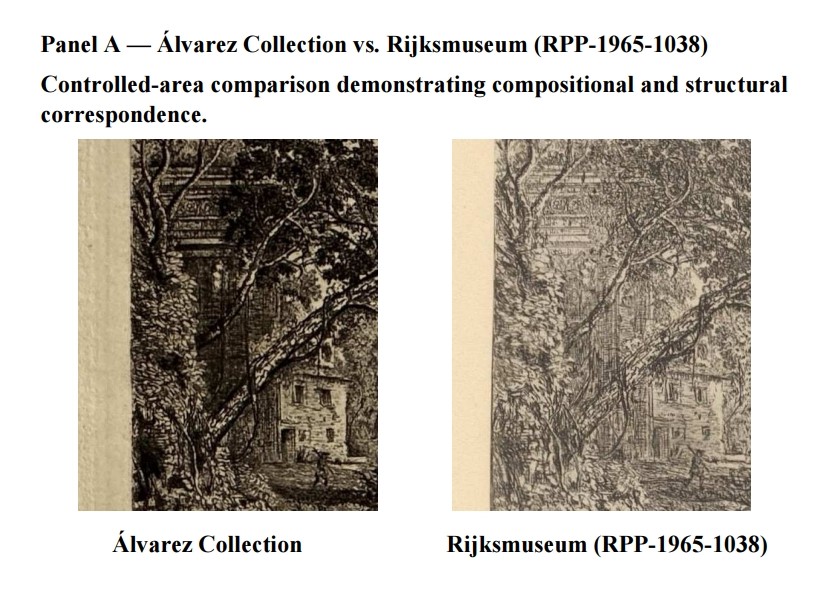

I. . Minute architectural detail — preserved line structure

at extreme magnification, architectural elements of nearly microscopic scale retain continuous engraved lines and functional ink deposition. The absence of line collapse, dotting, or tonal flattening confirms minimal plate wear and an early phase of printing. Such preservation of terminal-scale details is incompatible with later reprints or worn matrices and indicates exceptional material integrity of both plate and paper.

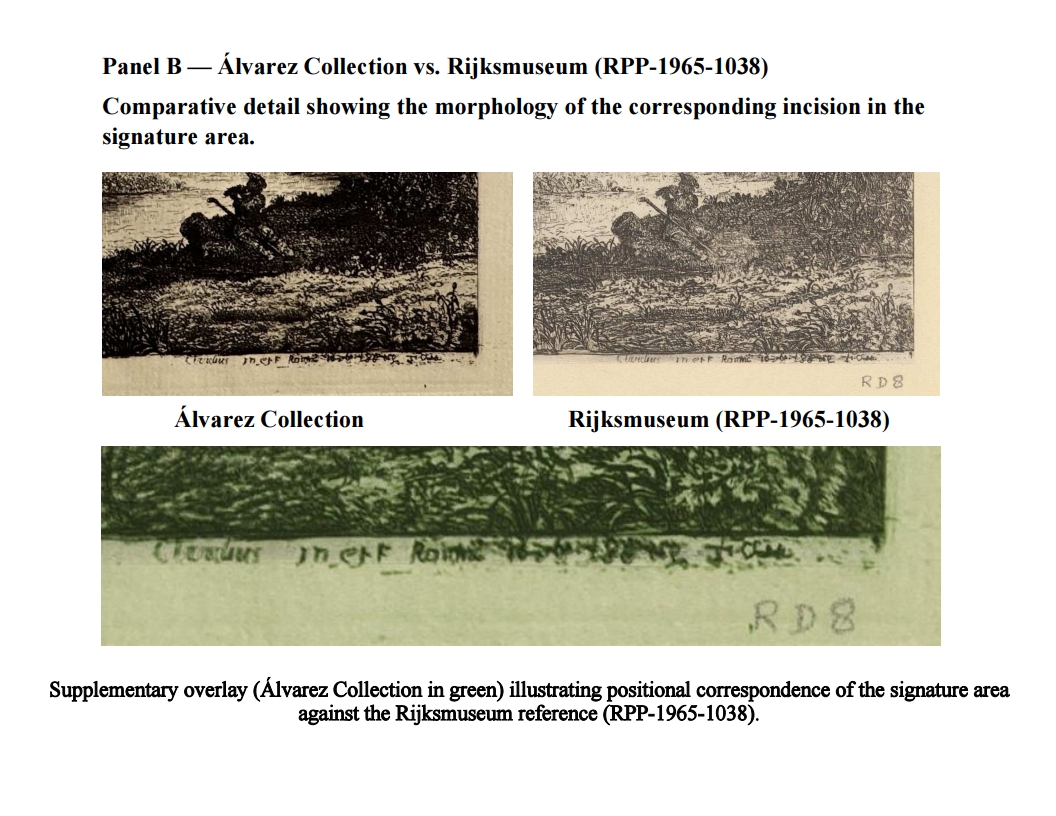

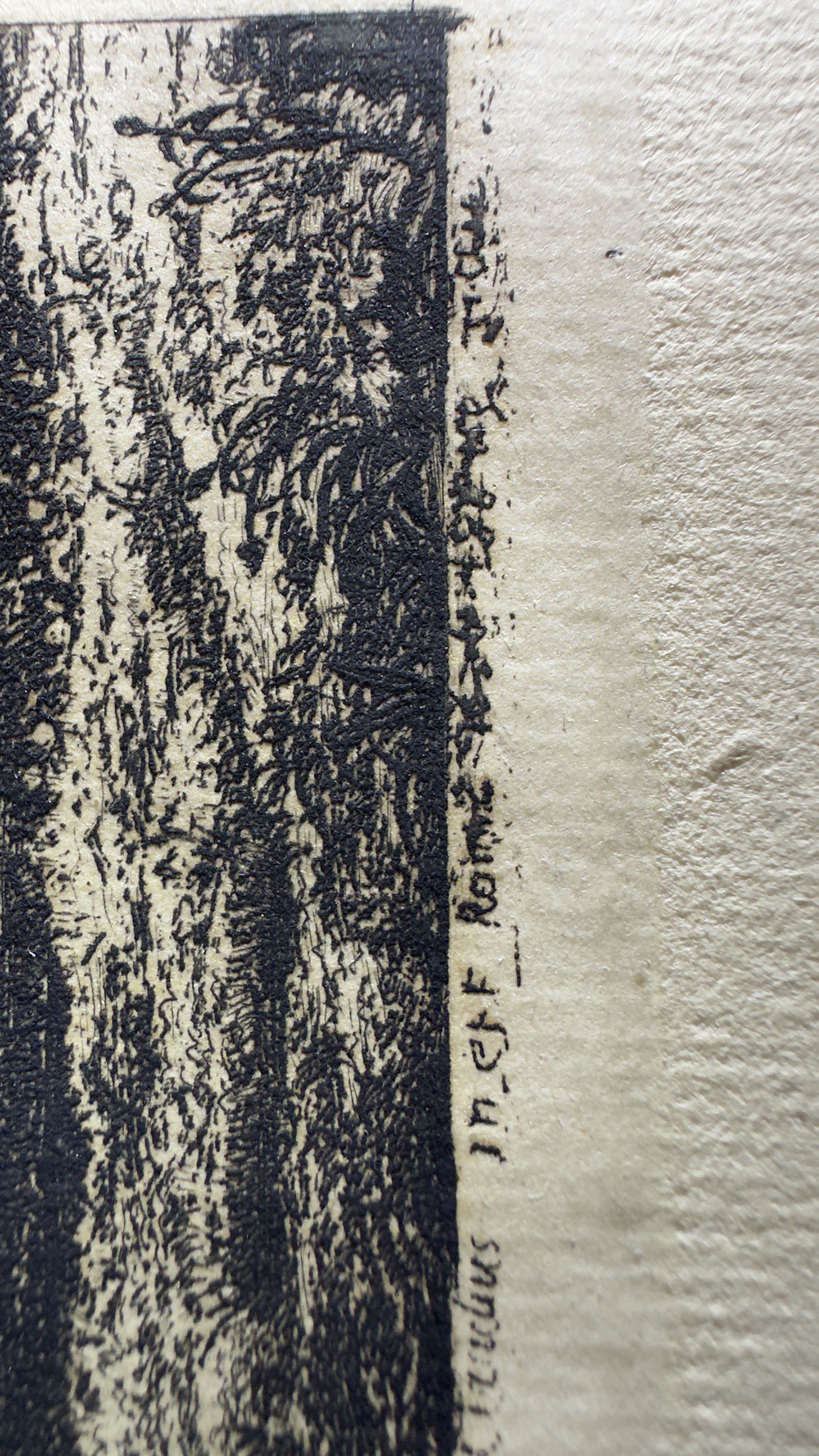

II. Signature macro (incision and ink–fiber interaction)

Macro detail of the artist’s signature Claudio in. Et f. Romae 1636 138 ne ficcen showing incised lines printed from the plate. The lettering exhibits irregular groove depth, localized burr retention, and heterogeneous ink deposition interacting with the paper fibers. These features indicate direct plate incision and manual inking, inconsistent with photomechanical or reproductive processes.

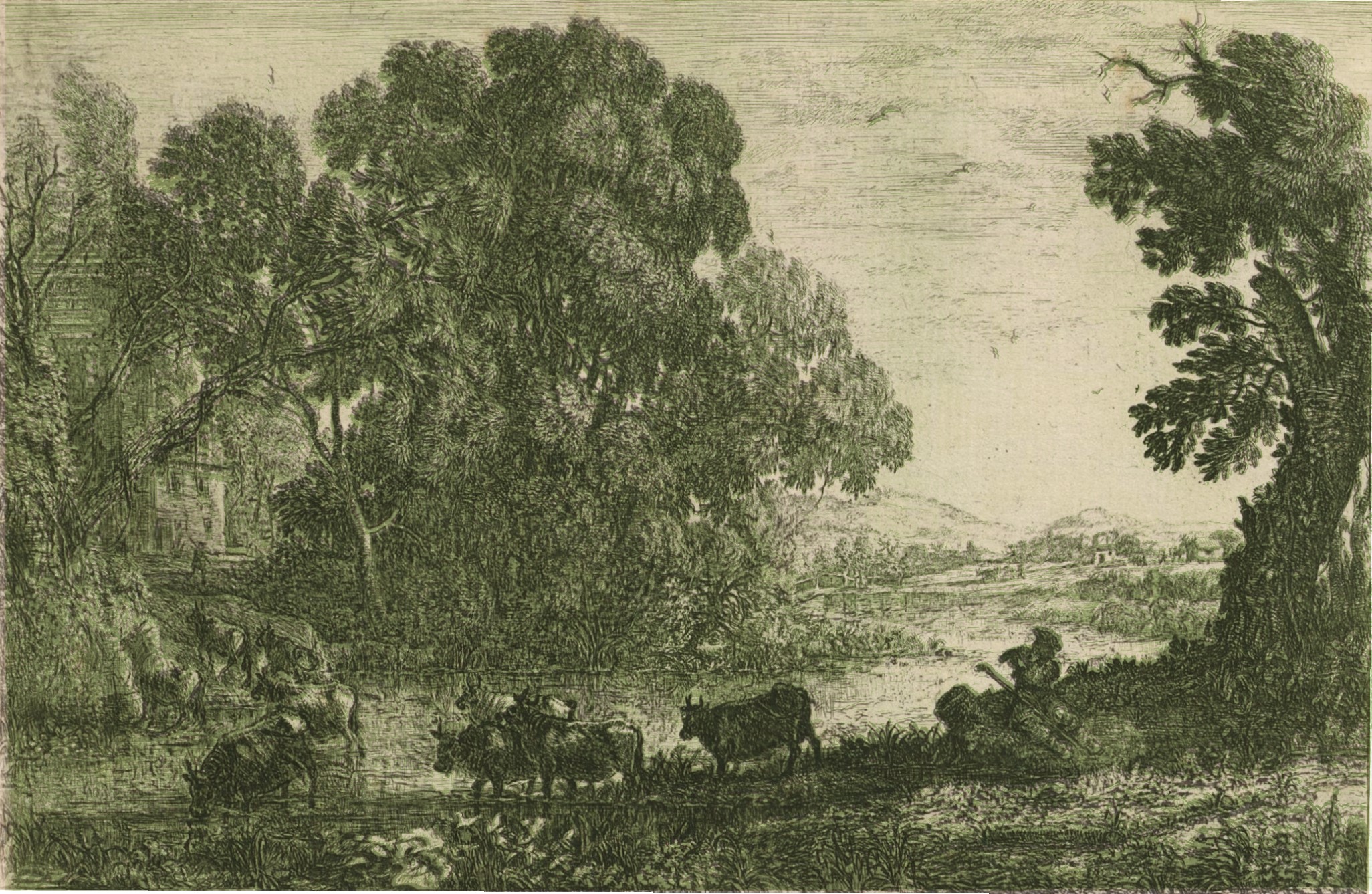

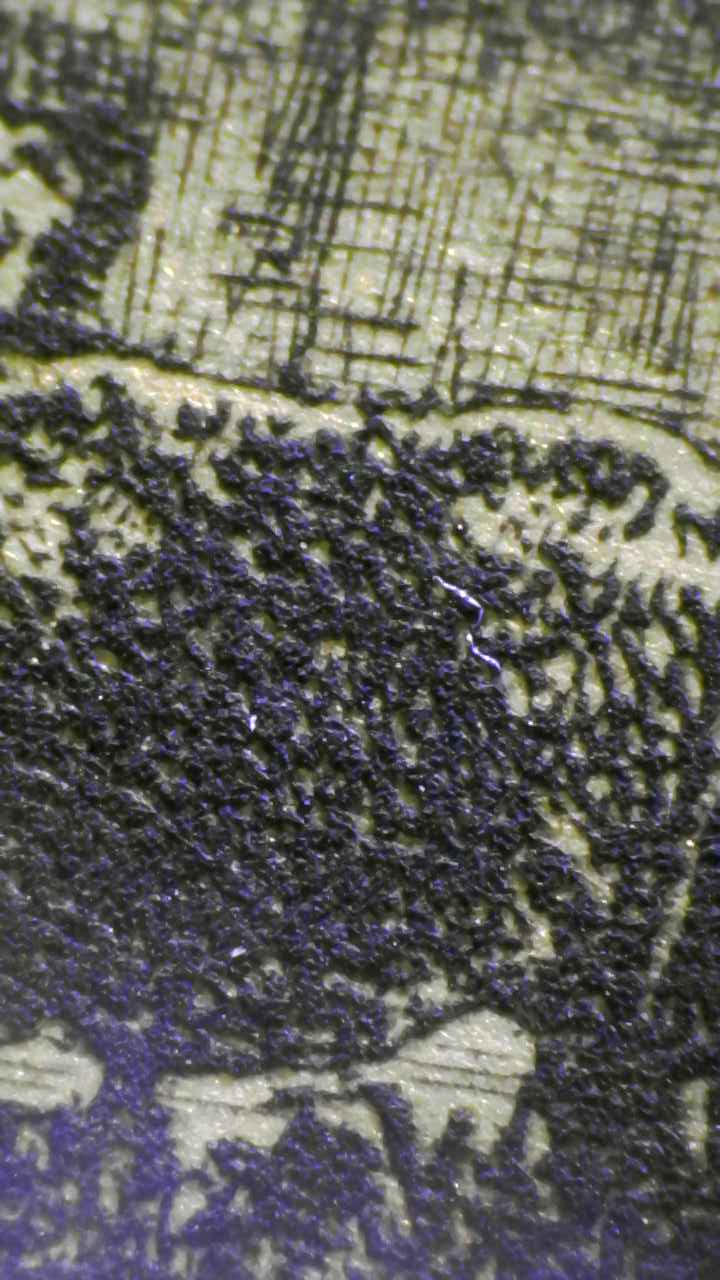

III. Arboreal structure — dense etched linework with residual burr

The foliage is constructed through a dense network of individually engraved lines, preserving their autonomy even in the darkest passages. Localized residual burr remains active along selected strokes, producing a velvety yet structurally legible black. The absence of tonal collapse or granular interference confirms printing from a minimally worn plate and excludes photomechanical or surface-based reproduction processes

.jpg)

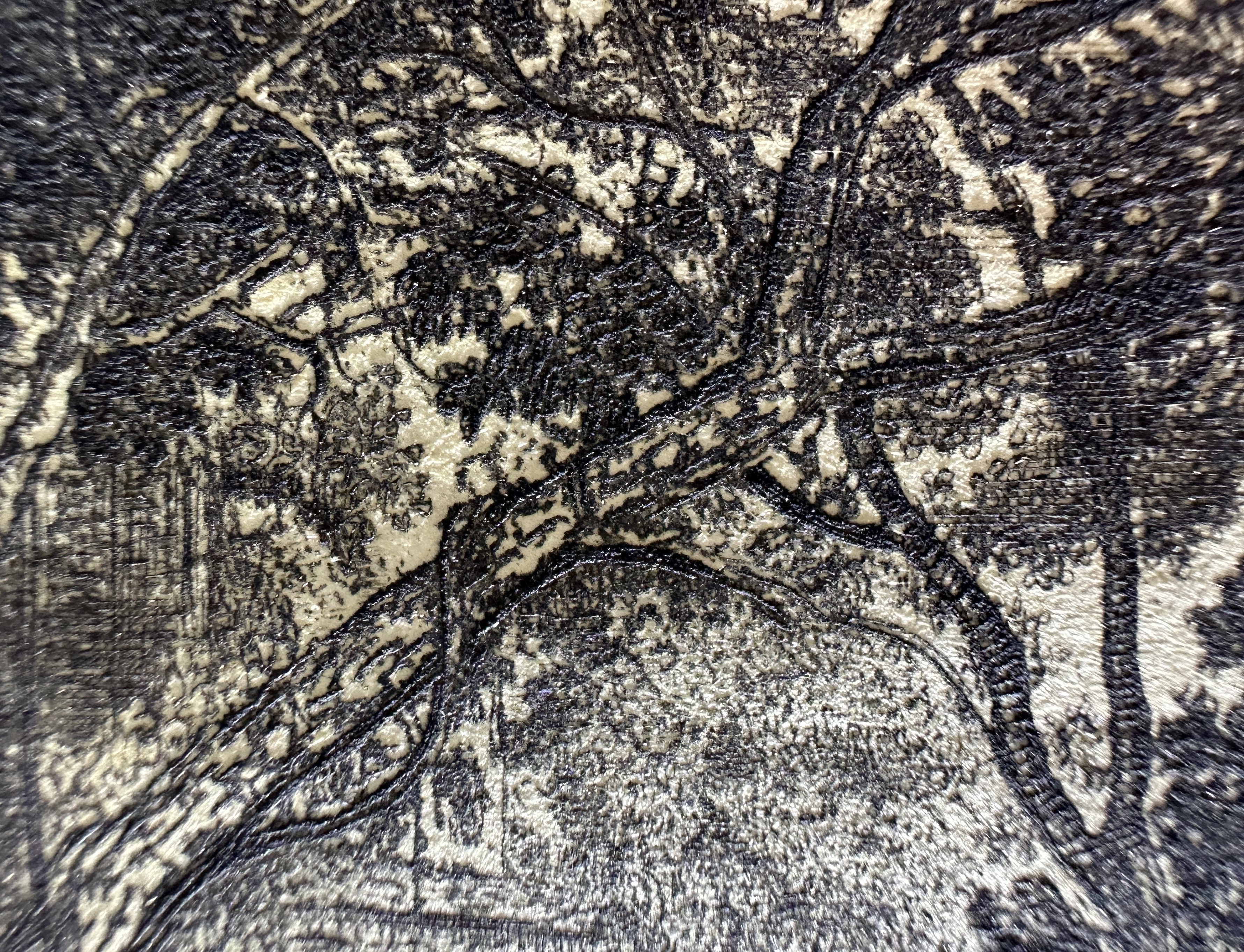

IV. Dense black tonal structure (residual drypoint burr)

A low, physically active drypoint burr preserved along selected engraved lines, integrated within the hatching structure and capable of retaining ink without collapsing line definition. This type of burr produces dense, matte blacks while remaining structurally stable and is consistent with early-stage printing from a minimally worn copper plate.

.jpg)

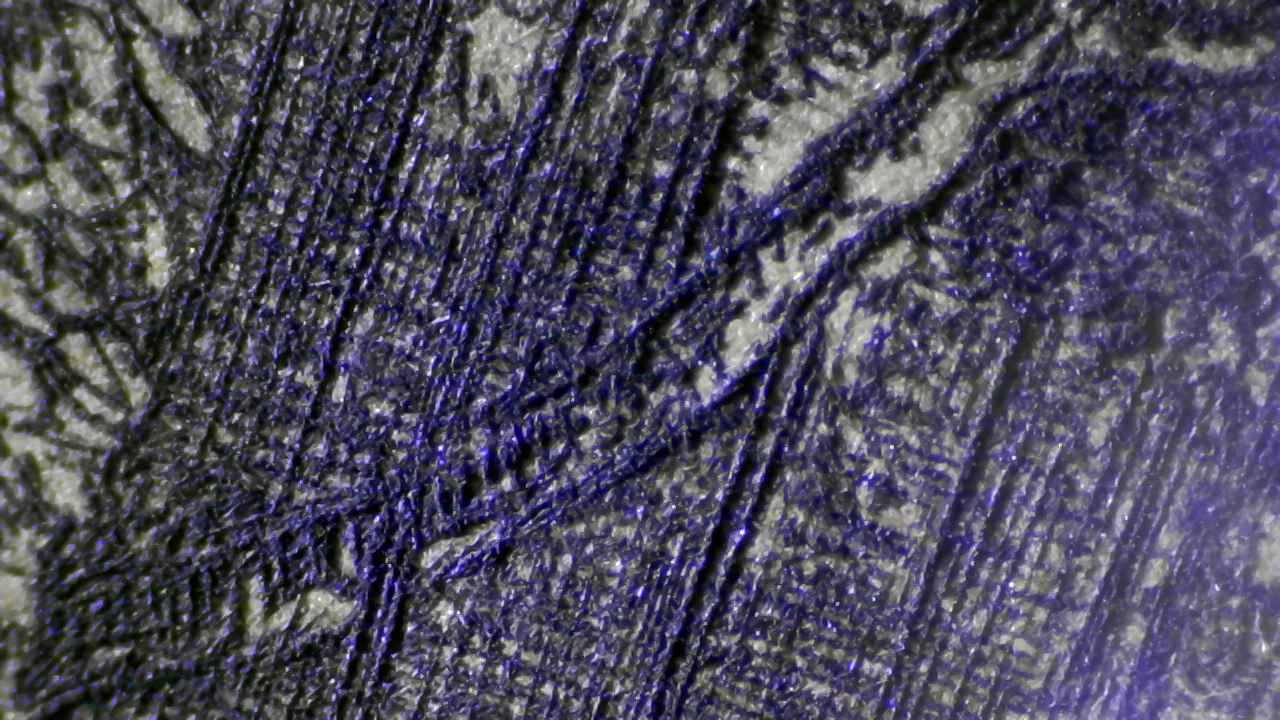

V. Arboreal hatching structure (intact engraved lines)

Macro examination of the arboreal forms reveals a dense hatching system composed of finely engraved, well-separated lines. Tonal depth is achieved through the accumulation and directional layering of incised strokes rather than through burr-dependent ink retention.

The grooves remain open and legible even in areas of high tonal density, indicating minimal plate wear and a printing phase within the active life of the copper plate. This structural clarity is fully consistent with Claude Lorrain’s controlled landscape engraving practice and is incompatible with later reprints, where line collapse and tonal flattening are typically observed.

.jpg)

VI. Figure modelling (ink squeeze and controlled plate tone)

Macro examination of the figural group reveals localized ink squeeze along engraved contours, produced by optimal press pressure and a well-balanced ink load. The slight displacement of ink against the edges of the grooves enhances tonal density without obscuring line definition.

A light, controlled plate tone is present across the figures and pedestal, contributing to volumetric modelling while remaining consistent with seventeenth-century intaglio printing practice. No excessive burr or tonal collapse is observed, indicating a well-preserved plate and an early phase of printing within the active life of the copper matrix.

VII. Figure modelling — exceptional ink pressure and preserved micro-relief

Macro examination of the figural passage reveals an exceptional convergence of controlled ink squeeze, light plate tone, and fully preserved micro-relief of the engraved lines. Ink displacement enhances volumetric modelling without obscuring line independence, while the paper remains fully responsive to the engraved grooves under press pressure.

The clarity of individual strokes within dense tonal passages indicates minimal plate wear and confirms printing during an early phase of the active life of the copper plate. This level of preservation is incompatible with later reprints or mechanically reproduced impressions.

Together, these observations demonstrate full material coherence between groove, ink, paper fibers, and press pressure, while the overlay comparison confirms structural identity with the institutional reference. No indicators of modern photomechanical reproduction are observed. The preservation of localized residual burr and intact support features is highly consistent with an early printing phase within the active life of the plate.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png?width=900)