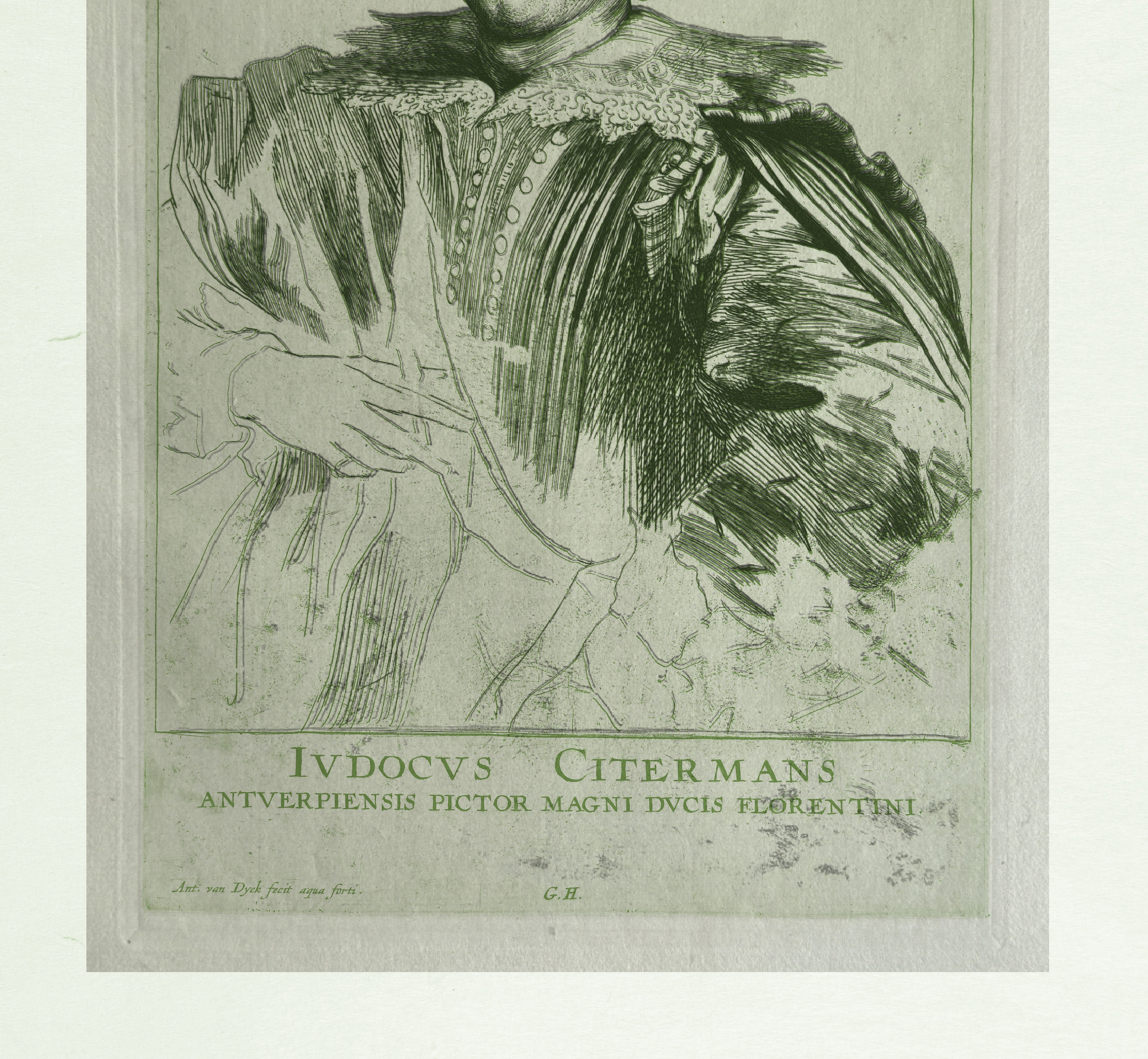

Justus Sustermans — Anthony van Dyck

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay analysis, and observation of organic degradation phenomena.

TECHNICAL DATA

- File ID

- AC-VD-242-REV-2026

- Artist

- Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

- Title

- Justus Sustermans

- Date of Execution

- C.1630-1632

- Technique / Materiality

- Etching on ivory laid paper.

- Dimensions

- Height 252 mm × Width 167 mm

- Sheet Dimensions

- Height 320 mm x Width 245 mm

- Sheet Weight

- 8 grams

- Collection

- The Álvarez Collection (Miami)

- Provenance

- Private family collection, preserved over generations

Research Objective

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay analysis, and observation of organic degradation phenomena.

Overall view showing composition, tonal balance, complete plate mark, and sheet margins.

Reverse side of the sheet under transmitted light, documenting the positioning structure and the overall response of the support. It shows a slight displacement of another intaglio print, consistent with prolonged storage under pressure. This phenomenon is typical of historical prints and confirms the physical nature of the printing process.

PAPER & WATERMARK

Physical properties of the paper support

The sheet measures 32.0 × 24.5 cm and weighs 9 grams, corresponding to an approximate paper density of c. 115 g/m². This value is consistent with a relatively robust laid paper suitable for intaglio printing and coherent with the observed fiber structure, thickness, and the mechanical response of the sheet to printing pressure.

The paper shows a clearly visible laid structure with both chain lines and laid lines typical of handmade rag paper. In printed areas, the surface exhibits localized compression and deformation, confirming that the sheet was printed damp and forced into the incised channels of the plate under pressure.

Fiber structure and sheet formation (microscopy)

Microscopic examination reveals a dense, irregularly interlaced fiber network composed of long fibers crossing and overlapping in multiple directions. The fibers are not aligned in a uniform or mechanical pattern but form a randomized, three-dimensional web, characteristic of a sheet formed in a vat from rag pulp.

Individual fibers can be observed passing over and under one another with variable thickness and length. There is no evidence of layered industrial sheet construction or short, matted wood-pulp fibers. The structure is therefore integrally felted, not stratified, and corresponds to handmade rag paper rather than to any continuous-machine product.

In printed passages, this interlaced network shows localized compression and displacement where the paper was driven into the incised grooves under press pressure; in unprinted areas the same open fibrous structure remains clearly visible. This behavior is consistent with true intaglio printing on a handmade support.

Embedded inclusions within the paper matrix

Microscopy also shows small colored fiber inclusions embedded within the paper matrix. These inclusions are not surface deposits but are structurally integrated into the sheet and therefore predate the printing of the image. Their presence is consistent with handmade rag paper in which incompletely disintegrated fiber fragments may remain incorporated during sheet formation.

UV examination

Under long-wave ultraviolet illumination, the paper support shows no bright blue-white fluorescence typical of modern optical brightening agents. Instead, the sheet presents a muted, uneven natural fluorescence consistent with uncoated, pre-industrial rag paper.

The UV response is structurally coherent across the sheet and does not indicate the presence of any modern coating layer or surface preparation. Local variations appear as minor tonal differences compatible with natural aging, handling, or superficial deposits.

Note: UV examination is used here as a material screening tool (presence/absence of modern brighteners and coatings) and is interpreted together with the laid structure, the microscopic fiber network, and the chain-line measurements.

Chain lines: spacing and structure

Systematic measurement of the chain-line intervals across the sheet yields the following sequence (in millimeters):

30 – 28 – 27 – 30 – 30 – 27 – 28 – 30

The spacing is not mechanically uniform but shows a structured and balanced rhythm with small variations (c. 27–30 mm), entirely consistent with a handmade mould in which the chain and laid wires are attached and tensioned by hand. The sequence displays bilateral balance around the central axis of the sheet rather than random or chaotic spacing.

Watermark placement and structural centering

The Fortuna watermark is positioned centrally within the chain-line structure. Its principal elements — the base, the circular motif, the figure, and the veil — align symmetrically with the underlying chain-line system and with the central axis of the sheet.

This configuration indicates that the sheet was not trimmed or oriented arbitrarily. The watermark, the chain-line structure, and the printed image are coherently aligned, implying deliberate orientation of the sheet with respect to the plate at the time of printing and careful selection and handling of the paper.

Relationship between support structure and printed image

The correspondence between:

- the rhythm of the chain-line spacing,

- the central placement of the Fortuna watermark, and

- the centering of the main compositional elements of the image

demonstrates a conscious relationship between the physical structure of the support and the placement of the printed plate. The paper is not a neutral or accidental carrier but an integrated component of the finished impression.

Summary (support evidence)

- Handmade laid rag paper

- Sheet size: 32.0 × 24.5 cm

- Weight: 9 g (≈ 115 g/m²)

- Clearly visible chain-line and laid-line structure

- Dense, three-dimensionally interlaced long-fiber network (vat-formed sheet)

- Embedded colored fiber inclusions within the paper matrix

- Fortuna watermark centrally positioned within the chain-line system

- UV response without optical brighteners, consistent with uncoated pre-industrial paper

- Mechanical response to printing pressure consistent with true intaglio printing

Taken together, these features define a high-quality handmade paper support appropriate for fine intaglio work and demonstrate a coherent, deliberate relationship between the sheet, its internal structure, and the printed image.

TECHNIQUE & STATE ANALYSIS

The present impression reveals, through systematic macro examination, a plate constructed and worked in clearly differentiated technical phases, and printed by true intaglio process.

At the most fundamental physical level, the impression shows ink seated inside incised channels, accompanied by pronounced ridge-and-valley relief and lateral compression of the paper fibers (“fiber squash”) along the edges of the strokes. This permanent deformation of the support can only be produced when a damp sheet is forced into the grooves of a metal plate under the pressure of an intaglio press. These features constitute direct physical evidence of authentic intaglio printing.

The tonal construction of the image is not uniform across the plate but is organized by pictorial zones, each employing a distinct technical language. In the garment, the dark masses are built through a dense system of layered hatching and cross-hatching, with strokes in multiple directions superimposed to progressively close the tone. The lines vary in depth, width, and ink load, revealing that the tone was developed in successive working stages rather than as a single, uniform operation.

By contrast, the facial areas are treated with a markedly different approach. Around the eye and in the flesh passages, the modeling is achieved through fine, curving etched lines combined with irregular stippling and fragmented strokes. The tonal structure here remains deliberately open, allowing the paper to remain visible and the form to be suggested rather than fully closed. This difference in graphic language indicates a conscious separation between structural tonal construction and sensitive facial modeling.

In the moustache and beard, a further layer of technical complexity becomes visible. The main forms are defined by deeper, more continuous and reinforced lines, while individual hairs and textures are articulated with finer, more irregular etched strokes. The superposition of these two types of marks reveals a sequential working process on the plate, in which structural contours were first established and subsequently enriched with secondary detail.

Particularly revealing is the transition zone between face and garment, where these different technical systems are integrated. Here, changes in line direction, groove depth, and ink load can be observed within a very small area, together with intermediate adjustment strokes. This zone exposes the internal architecture of the plate and shows how the artist progressively assembled the image by coordinating distinct working phases rather than executing it in a single, homogeneous pass.

A further macro view of the facial and neck area demonstrates the simultaneous use of three distinct technical languages within a single pictorial field: stippling and fine open etching for the flesh, and dense hatching and cross-hatching for the darker masses of the neck and garment. The clear differences in stroke character and incision depth confirm that the plate was being developed in stages and that multiple modes of work coexist in this state.

Across all these areas, the groove edges remain sharp and the relief well preserved, with no generalized rounding or collapse of the channels. This indicates a plate that had not yet undergone significant wear at the time this impression was printed.

Taken together, these observations show that the plate was not yet in a fully standardized, closed production state. Instead, it preserves clear evidence of a progressive, exploratory working process: tonal fields in different degrees of completion, open and closed passages coexisting, and visible adjustments in the integration of forms. From a strictly material and technical standpoint, the impression corresponds to a working or early state of the plate, consistent with a proof taken during the development of the composition rather than from a later, fully finalized state.

High-magnification macro view showing ink seated inside the incised channels and a clear lateral compression of the paper fibers at the edges of the dark strokes (“fiber squash”). This plastic deformation of the support is produced when the damp sheet is forced into the grooves under the pressure of the intaglio press and constitutes direct physical evidence of true intaglio printing. The sharp groove edges and the pronounced fiber displacement further indicate a plate in an early stage of use.

High-magnification macro view of the garment showing a dense system of layered hatching and cross-hatching strokes, built up in successive passes to construct the dark tone. The lines display varying depth, width, and ink load, indicating a progressive working process on the plate rather than a single, uniform stage. The presence of residual paper openings between strokes shows that the tonal field was still being developed, consistent with a working or early stage of the plate.

High-magnification macro view of the eye area showing fine, curving etched lines combined with fragmented strokes and irregular dot-like ink deposits to model form and expression. Unlike the dense cross-hatching used in the garment, the facial features are constructed with an open tonal structure that allows the paper to remain visible. The ink is seated within the incised channels, and the surrounding paper shows pressure-induced deformation, confirming intaglio printing and indicating an early, working stage of the plate.

High-magnification macro view of the moustache and beard area showing the combined use of deep, continuous reinforced lines to define the main forms and finer, more irregular etched strokes to articulate individual hairs and surface texture. The superposition of these different types of marks reveals a sequential working process on the plate rather than a single, uniform execution stage. The ink is seated within the incised channels and the surrounding paper shows pressure-induced deformation, confirming true intaglio printing and supporting an early, working stage of the plate.

High-magnification macro view of the transition area between the face and the garment, showing the integration of two distinct technical languages: fine, open etched lines and stippled marks for the flesh, and dense hatching and cross-hatching for the clothing. The change in line direction, groove depth, and ink load reveals a step-by-step construction of the plate and the presence of intermediate adjustment strokes. The ink is seated within the incised channels and the paper shows pressure-induced deformation, confirming true intaglio printing and supporting a working or early stage of the plate.

High-magnification macro view of the hand showing long, open, structural etched lines used to establish form and gesture rather than to build a finished tonal field. The absence of dense hatching and the presence of largely unclosed passages indicate that this area of the plate was still in a constructive phase at the time of printing. The ink is seated within the incised channels and the paper shows pressure-induced deformation, confirming true intaglio printing and supporting a working or early stage of the plate.

MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION

Microscopic examination shows that the image is constructed entirely through systems of incised lines rather than through tonal or surface-based processes. At high magnification, every dark passage resolves into individual grooves with clearly defined channels, demonstrating that the tonal values are produced by the density, direction, and superposition of engraved strokes rather than by any continuous tone.

Parallel groove systems with visible channel morphology (Fig. 1) confirm the use of line-based incision as the primary constructive element. In darker passages, these lines are crossed by dense counter-directional hatching (Fig. 2), increasing optical density through systematic superposition. In curved and rounded forms, the shading is built from bundles of parallel curved grooves arranged in spiral or arcing structures (Fig. 3), showing deliberate modulation of direction to describe volume.

Facial modelling is achieved through the layered combination of curved incised lines and point-based marks (Fig. 4), producing smooth tonal transitions without any flat or mechanically uniform areas. Elsewhere, superimposed engraved strokes form complex curved modelling lines (Fig. 5), revealing successive passes of the tool rather than a single uniform action.

Circular and rounded elements are not mechanically drawn shapes but are constructed manually, stroke by stroke, from sequences of short engraved segments (Fig. 6), each with its own orientation and depth. This confirms that forms are built additively through line construction rather than outlined and filled.

Across all examined areas, the microscopic structure is consistent: tone, volume, and form are produced exclusively by the controlled accumulation, crossing, and layering of individual incised strokes. No evidence of tonal washes, surface abrasion, or photomechanical processes is present. The image is therefore structurally defined by a fully line-based engraving system.

Microscopic view showing a field of closely spaced, mostly parallel incised grooves. Each line appears as an individual channel with clearly readable continuity and variable width. The ink is confined inside these channels, while the lighter bands between them expose the paper fiber network. Several grooves show slight irregularities along their edges, including local widening, narrowing, and small discontinuities, indicating separate tool passes rather than a mechanically uniform process. The boundaries of each groove remain distinct and do not merge into a continuous surface tone. The tonal effect is therefore produced by the cumulative density of individual incised channels rather than by any filled or flat area.

Microscopic view showing a second system of closely spaced incised lines laid in a different direction from the underlying strokes. The lines are packed at a much shorter interval, forming a dense hatching layer that crosses or overlays the previous system. Each line remains individually readable as an incised channel filled with ink. The tonal darkening is produced by the superposition and high density of these closely spaced strokes rather than by any continuous or bitten surface.

Microscopic view showing groups of closely spaced, curved incised grooves arranged in repeated spiral and hook-like patterns. Each structure is built from multiple parallel lines following a common curvature, with slight variations in spacing, depth, and width between individual grooves. The ink is retained inside each channel, while the lighter areas between lines expose the paper fiber network. The tonal effect is produced by the progressive densification and overlap of these curved line bundles rather than by any continuous or filled surface. Each spiral element is therefore constructed by a sequence of discrete tool passes following a controlled curved trajectory.

Microscopic view of the facial area showing modelling constructed by superposition of curved incised lines combined with numerous discrete point-like marks. The darker zones are formed by dense accumulation of individual grooves following the anatomical curvature of the eyes and brow, while the lighter central area is defined by a lower density of lines and a higher visibility of the paper fiber network. The points visible in the mid-tones are isolated, non-connected marks, each corresponding to a separate tool action. The ink remains confined inside the incised channels, whose individual paths and overlaps are clearly readable at this scale. The overall tonal transition is produced by progressive variation in line density and point distribution rather than by any continuous or uniform surface tone.

Microscopic view of a group of curved lines constructed by multiple superimposed engraved strokes. Each visible line is not a single pass, but the result of several closely spaced tool movements that partially overlap. The individual grooves remain distinguishable, with variable width, depth, and spacing. Ink accumulates preferentially inside the incised channels, while the surrounding paper fibers remain visible between strokes. The modelling of the form is achieved by the progressive addition of parallel and slightly diverging lines rather than by a continuous or mechanically uniform trace.

Microscopic view of several circular forms constructed from multiple individual curved engraved strokes rather than from a single continuous line. Each circle is composed of short, overlapping line segments with clearly visible junctions and changes in direction. The inked grooves show strong local relief, with ink accumulation varying from stroke to stroke. The surrounding area is filled with dense, parallel hatching lines that maintain their individual channel structure and do not merge into a flat tone. The paper fiber network is clearly visible in the lighter interior of the circles and between strokes. The geometry of the circles is therefore not mechanically regular, but the result of repeated manual tool passes, each leaving a distinct engraved channel.

DIGITAL OVERLAY AND COMPARISON WITH THE MUSEUM PIECE

A direct digital overlay was performed between Álvarez's print and the institutional reference preserved at the Rijksmuseum (RP-P-BI-7411), using uniform proportional scaling and alignment based on structural axes (horizon line, tree masses, main figures, and plate outline). No deformations, optical distortions, or interpretive adjustments were applied.

The overlay confirms the structural identity of the matrix: the plate outline and internal proportional relationships coincide precisely. The observable differences are limited to the inscription at the bottom of the work (RP-P-BI-7411), which is absent in the Álvarez print due to the difference in the state of the work.

Structural overlay of the complete composition between the Álvarez impression and the institutional reference held at the Rijksmuseum (RP-P-BI-7411). The green layer corresponds to the Rijksmuseum impression, while the underlying image corresponds to the Álvarez sheet. The coincidence of the plate outline, internal proportions, and all principal compositional elements demonstrates full structural identity of the copper matrix across the entire image.

Structural overlay of the facial area between the Álvarez impression and the institutional reference held at the Rijksmuseum (RP-P-BI-7411). The green layer corresponds to the Rijksmuseum impression, while the underlying image corresponds to the Álvarez sheet. The coincidence of contours, internal modelling lines, and tonal structures demonstrates complete structural identity of the copper matrix in the most sensitive area of the composition.

A direct overlay comparison between the Álvarez impression and the institutional reference held at the Rijksmuseum (RP-P-BI-7411). The green layer corresponds to the Rijksmuseum impression, demonstrates complete structural coincidence of the pictorial field and plate geometry. The only material divergence lies in the engraved inscription, which is present in the Rijksmuseum impression and entirely absent in the Álvarez sheet. This shows that the inscription corresponds to a later intervention on the same copper matrix, while the Álvarez impression preserves the plate before this modification.

Provenance and History

The print was transmitted from generation to generation, remaining within the same family. Its state of preservation suggests minimal historical handling: it was stored for decades in a protected environment, away from direct light and damaging humidity fluctuations. It is likely that the print has been handled far less during the past one hundred years than during the recent technical examination conducted under microscopy, raking light, and transmitted-light watermark analysis.

This continuity of private custody—without recorded sales, auction appearances, or dealer interventions—helps explain the exceptional condition of the sheet and the survival of fragile physical features often lost in circulating impressions, including residual micro-relief, intact margins, and a fully preserved watermark.

Provenance therefore supports attribution not only through lineage, but through material coherence: every aspect of the sheet’s condition aligns with an impression that has remained intact and undisturbed since the seventeenth century.

References

Ash, Nancy & Fletcher, Shelley. Watermarks in Rembrandt’s Prints. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1998.

Cited as a key technical reference for Fortuna watermark typologies in seventeenth-century print contexts.

Rembrandt WIRE Project (Cornell University). Ongoing digital watermark imaging and census research.

Referenced here for comparative framework on watermark documentation practices (methodological context).

Portret van Justus Sustermans met onderschrift IVDOCVS CITERMANS ANTVERPIENSIS PICTOR MAGNI DVCIS FLORENTINI New Hollstein Dutch 11-3(5)

Mauquoy-Hendricx (van Dyck) 12-3(5)

Access and research collaboration

High-resolution files, complete macro-photography sets, and the internal technical dossier for the Álvarez impression of Justus Sustermans are available to researchers upon request. Comparative video-microscopy sessions can also be arranged for institutions interested in examining in detail the physical features associated with early phases of plate use.

All observations presented on this page are based on direct examination of the private impression and on published images from institutional collections. Attribution, dating, and official terminology remain open to academic discussion and are offered here as a contribution to ongoing research on Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) prints.

For inquiries, image permissions, or collaborative research projects, please use the contact form on the main website or write to:

susana123.sd@gmail.com

fineartoldmasters9919@gmail.com

susana@alvarezart.info

Phone: +1 786 554 2925 / +1 305 690 2148

Álvarez Collection Verification Record #AC-VD-242-REV-2026