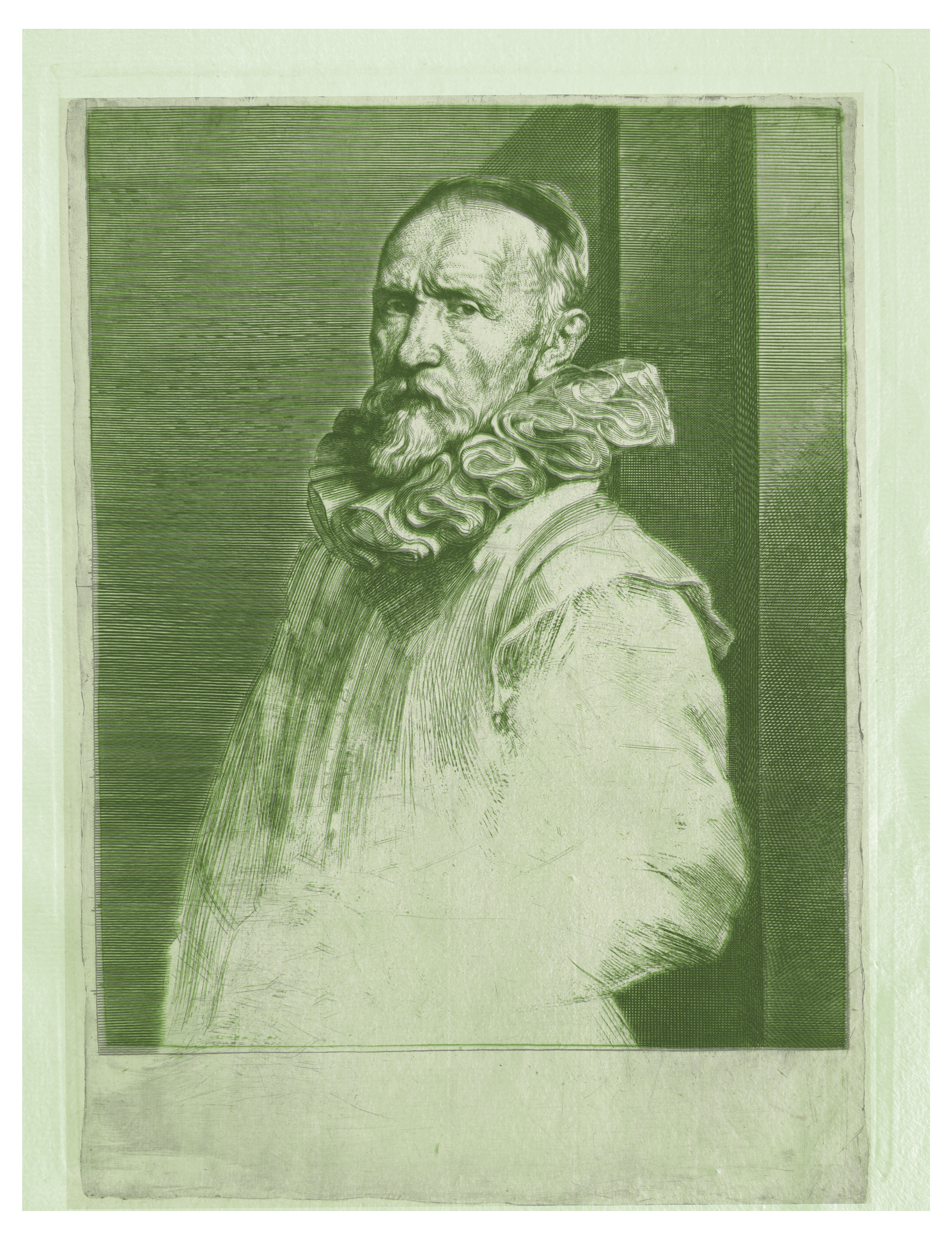

Jan de Wael — Anthony van Dyck

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay analysis, and observation of organic degradation phenomena.

TECHNICAL DATA

- File ID

- AC-VD-243-REV-2026

- Artist

- Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

- Title

- Jan de Wael

- Date of Execution

- C.1630-1632

- Technique / Materiality

- Etching on ivory laid paper.

- Dimensions

- Height 249 mm × Width 176 mm

- Sheet Dimensions

- Height 320 mm x Width 245 mm

- Sheet Weight

- 8 grams

- Collection

- The Álvarez Collection (Miami)

- Provenance

- Private family collection, preserved over generations

Research Objective

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay analysis, and observation of organic degradation phenomena.

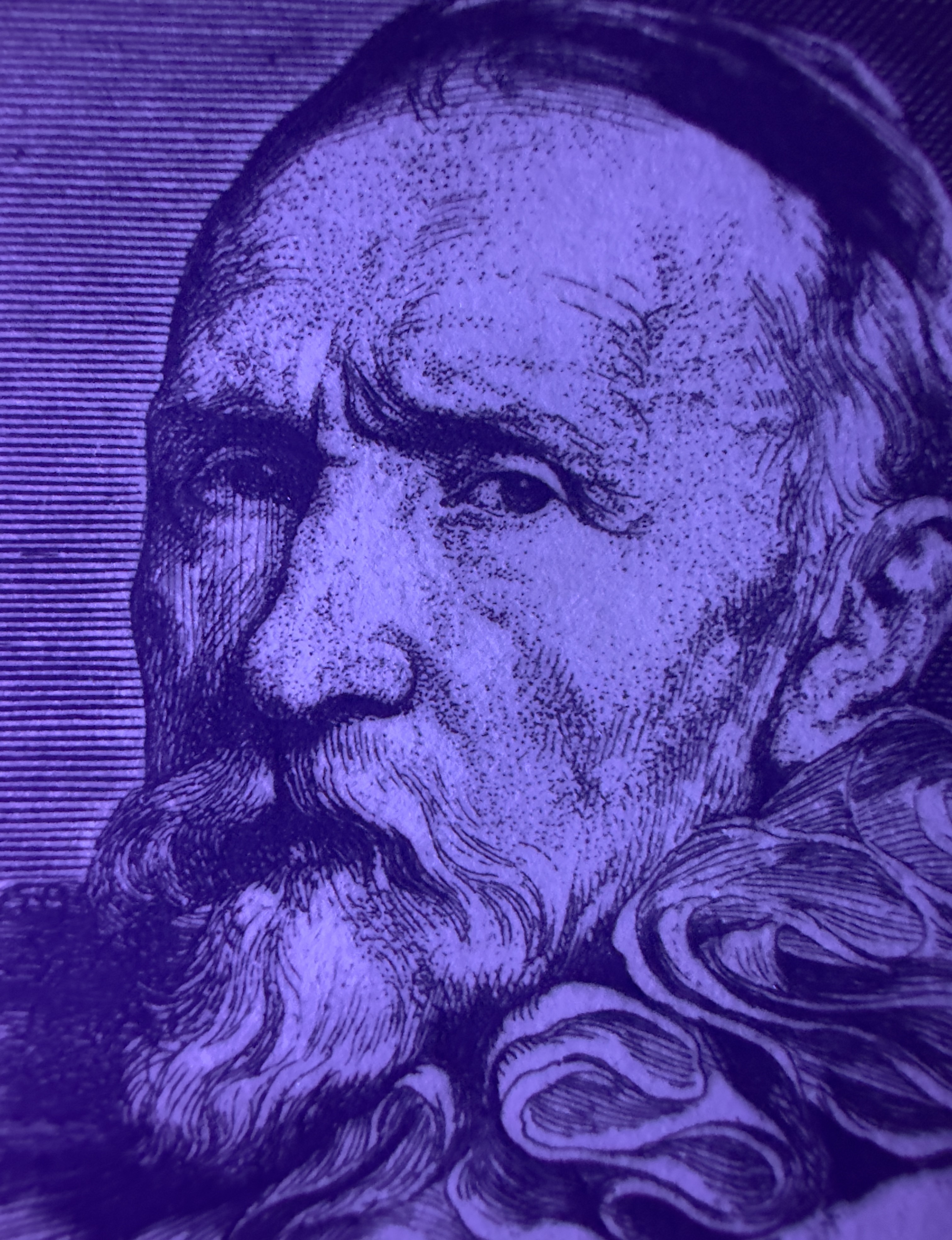

Overall view showing composition, tonal balance, plate mark coherence, and sheet margins.

Reverse side of the sheet under transmitted light, documenting laid structure and watermark visibility.

PAPER AND WATERMARK ANALYSIS

The present impression is printed on seventeenth-century laid (vergé) paper bearing a PvL.a countermark, documented through transmitted light, macro photography, and ultraviolet examination. The physical structure of the support, its internal fiber network, and its optical response under UV illumination are fully consistent with early modern rag paper production.

I. Laid structure and chain-line spacing

Transmitted-light examination reveals a clearly defined laid structure with regular chain lines. The measured spacing shows a variable rhythm of approximately 28–30 mm (sequence observed: 28–28–28–30–30–28–28–30 mm), entirely consistent with seventeenth-century handmade paper produced on laid molds. This type of irregular yet rhythmic spacing is characteristic of hand-assembled wire molds and excludes any modern or industrial paper production process.

II. Watermark / Countermark: PvL.a

The sheet bears a PvL.a countermark, visible under transmitted light and documented in full. The mark is structurally coherent with early Van der Ley papermaking traditions and is fully integrated into the paper matrix, not applied or altered post-production.

Its presence in this impression, combined with the technical and stylistic dating of the plate to the early 1630s, confirms that this paper type was already in circulation during that period.

III. Fiber structure and paper body

Microscopic examination of the paper surface shows a dense, irregular network of rag fibers, with no evidence of industrial cutting, chemical pulping, or modern fillers. The fibers are long, organically interwoven, and show natural variability in thickness and orientation.

Ink penetration follows the fiber structure of the sheet, demonstrating true mechanical integration between ink and support, as expected in early handmade rag paper printed under intaglio press pressure.

IV. Ultraviolet response

Under low-intensity ultraviolet illumination, the paper exhibits a muted, homogeneous response consistent with historic rag paper. No localized fluorescence anomalies are observed that would indicate:

- Modern optical brighteners

- Synthetic sizing agents

- Retouching, patching, or restoration

- Later paper interventions

The plate mark area appears as a zone of altered fiber density, consistent with mechanical compression from intaglio printing.

Conclusion

All observed features — laid structure, chain-line rhythm, PvL.a countermark, fiber morphology, and ultraviolet behavior — are fully coherent with seventeenth-century handmade rag paper and with an early printing phase of the plate. The support shows no evidence of later manipulation, washing, or modern intervention, and its material characteristics are in complete agreement with the historical and technical context of Van Dyck printmaking activity in the early 1630s.

MACROGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

The organization of the line systems anticipates the visual language later used in security engraving, where tone and volume are constructed exclusively by dense, interlaced line structures rather than by surface shading.

The macro graphic examination reveals a printing process of exceptional technical coherence and control. Tone is constructed not through flat ink areas but through a highly organized architecture of hatching and cross-hatching, in which the accumulation, orientation, and spacing of engraved lines generate both volume and depth while preserving full legibility of individual strokes, even in the densest passages.

In the modelling of the face and flesh areas, the artist integrates short strokes with point-like marks to achieve subtle tonal transitions. This combined use of linear shading and controlled stippling produces continuous gradations without mechanical repetition, confirming manual incision and deliberate tonal orchestration.

Several details demonstrate the physical nature of the intaglio process. The ink is seated inside the engraved grooves, and the surrounding paper fibers show clear lateral compression and flattening along the line edges. This deformation of the paper surface results from the damp sheet being forced into the incised channels under the pressure of the press and constitutes direct material evidence of true intaglio printing.

The printed lines retain a three-dimensional character: their edges remain physically active, with a preserved micro-relief rising above the surrounding paper surface. The strokes are not planar deposits of ink but volumetric structures transferred from the incised copper plate, maintaining sharp boundaries and directional coherence.

Finally, the continuity of ultra-fine strokes and the absence of line collapse or filling-in indicate minimal plate wear and an exceptionally well-preserved working state of the plate. The overall macro graphic evidence confirms a fully coherent intaglio process.

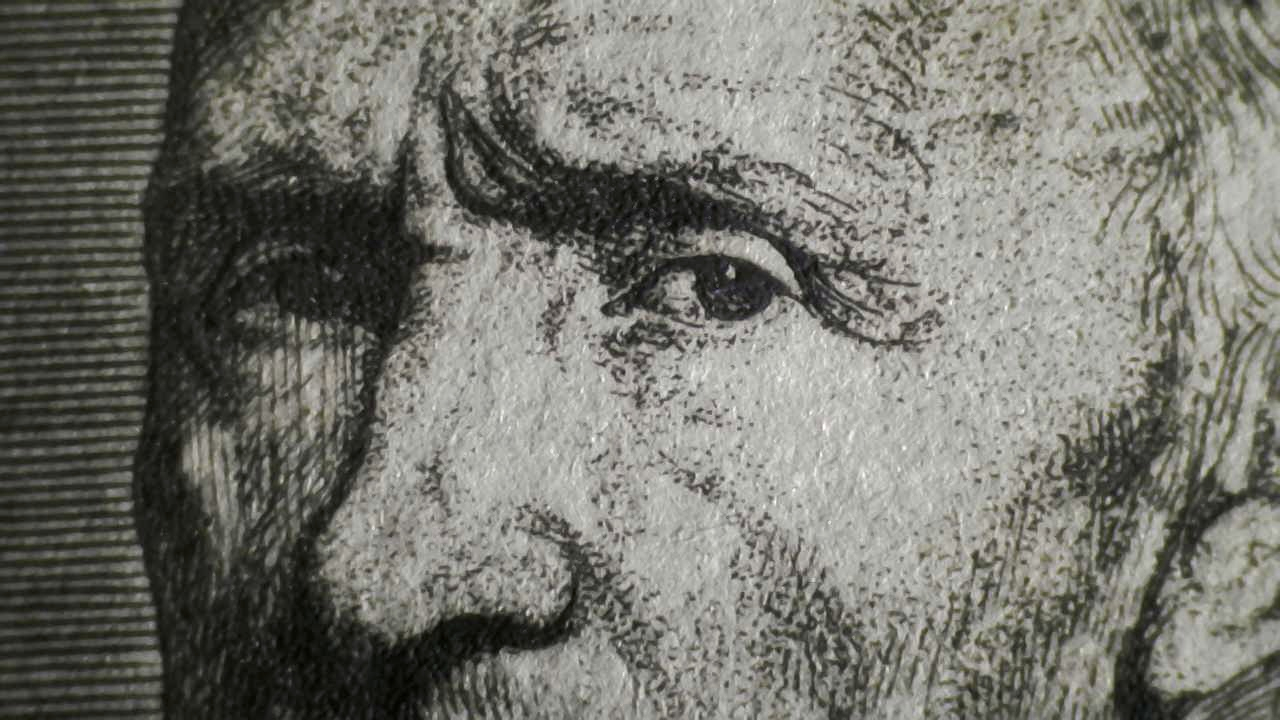

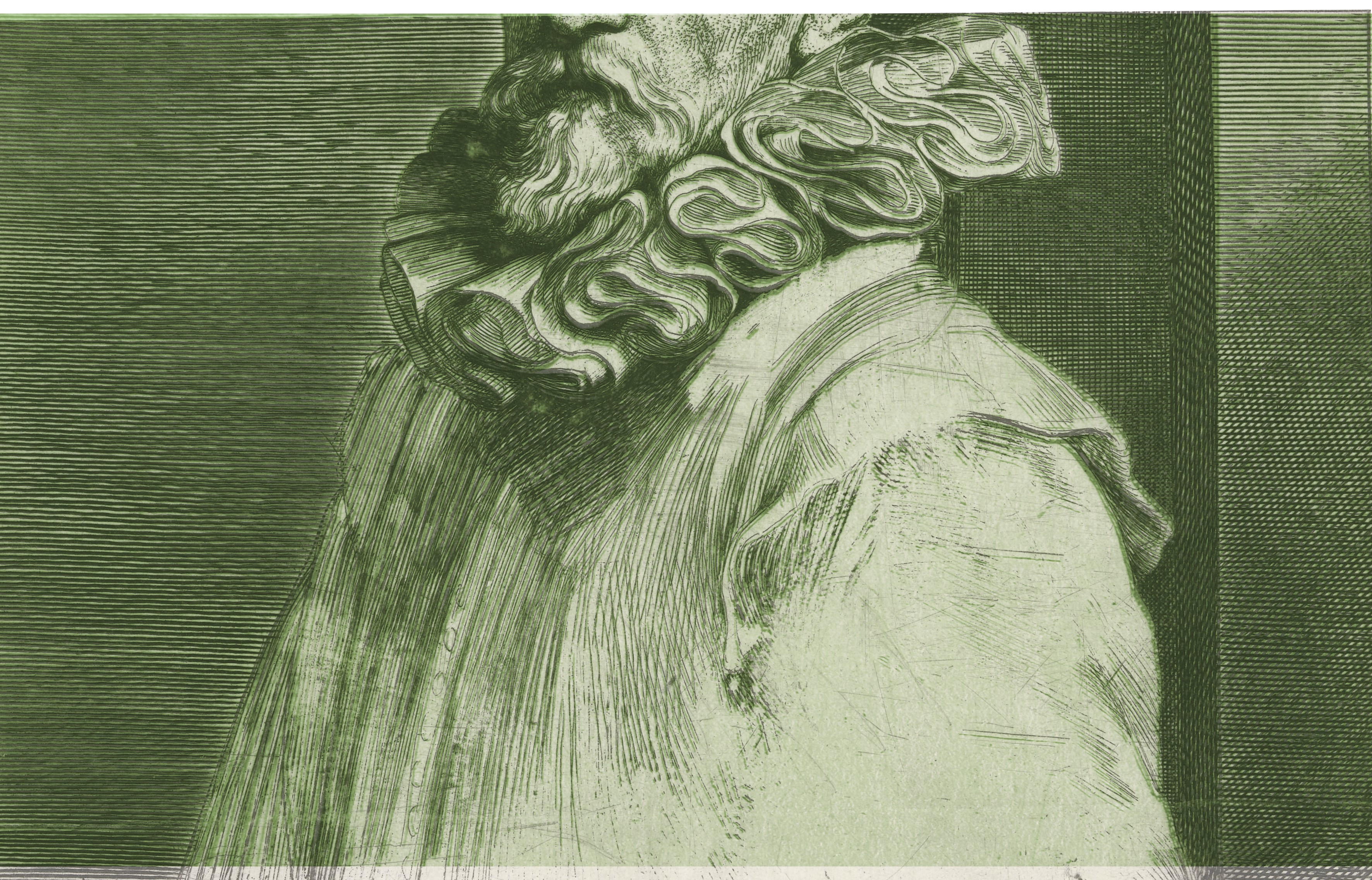

High-magnification macro view showing a tonal field constructed through a highly disciplined system of parallel hatching and cross-hatching lines. The strokes are laid with uniform spacing and consistent orientation within each directional layer, and the tonal density is achieved exclusively by the superposition and crossing of these linear systems rather than by surface tone or mechanical shading. Each individual line remains clearly readable, with ink seated inside the incised channels and no evidence of surface-based or photomechanical processes. The result is a structurally coherent, optically dense tonal field built entirely through controlled line architecture, characteristic of Van Dyck’s precise and methodical intaglio technique.

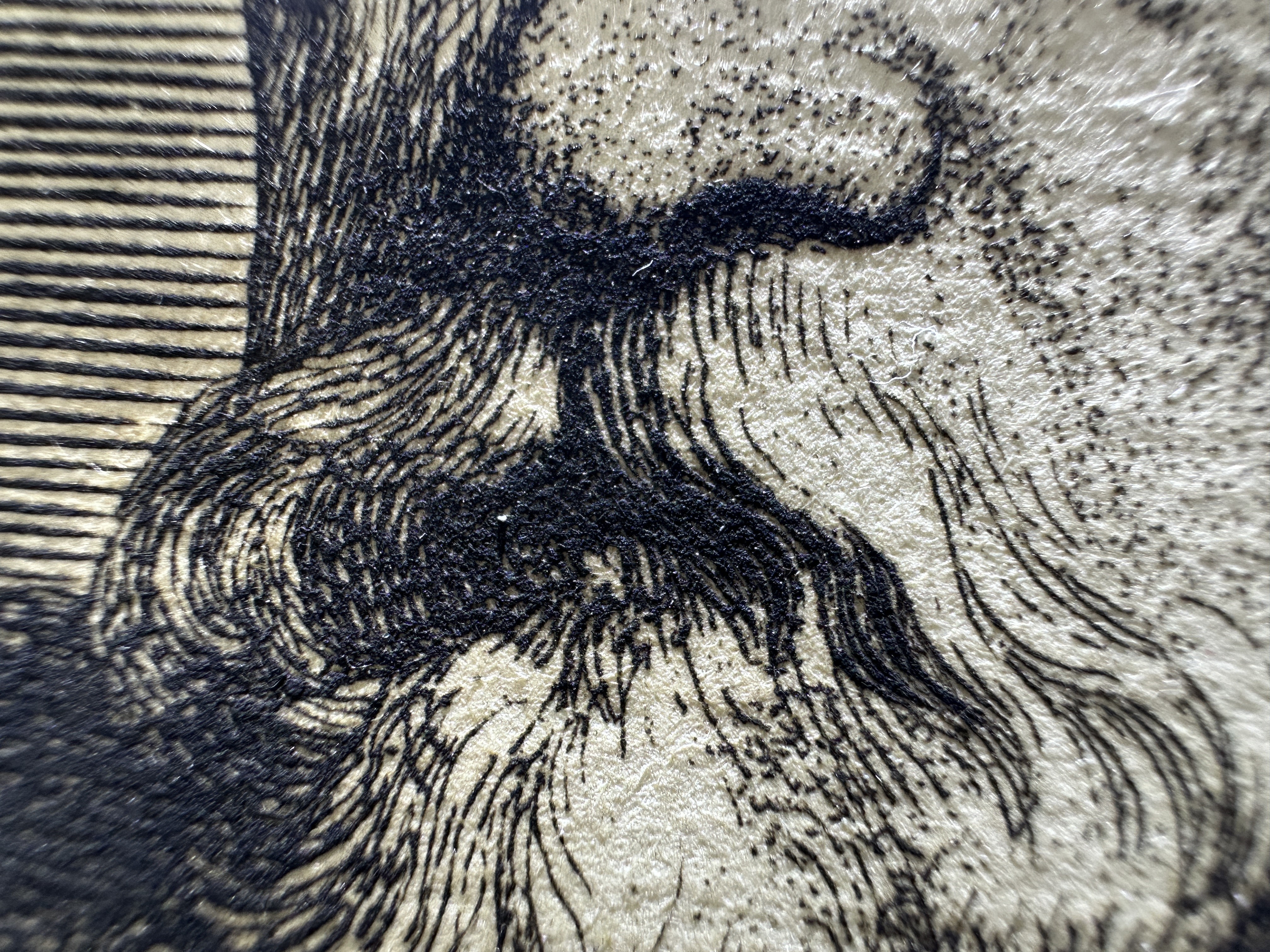

High-magnification macro view of the facial area showing modelling constructed through a dense system of stippling (point-based marks) combined with extremely fine etched lines. The tonal transitions are achieved by varying the density of points and the superposition of delicate linear strokes rather than by any continuous surface tone. The paper remains visible in the lighter zones, while the darker areas are built through progressive densification of discrete marks. The ink is seated within the incised lines and in the microscopic point-like impressions, and the surrounding paper fibers show localized compression, confirming true intaglio printing. This technique demonstrates Van Dyck’s controlled and economical use of point and line to describe form with exceptional subtlety.

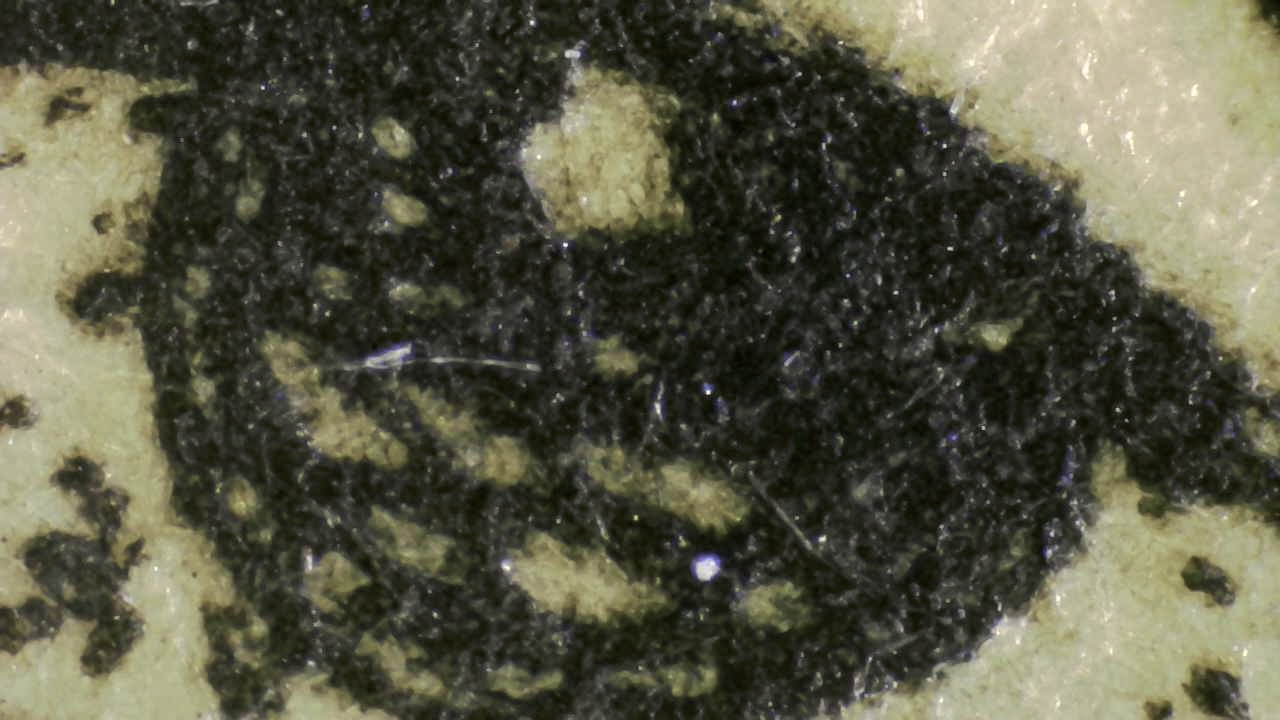

High-magnification macro view showing a zone of extreme tonal density constructed through the superposition of stippling and multiple layers of fine etched lines. The dark mass is not the result of surface tone or uncontrolled biting, but of a progressive accumulation of discrete point-based marks and closely spaced incised strokes. Individual lines remain structurally legible at the edges of the dense area, and the boundaries of the incised channels remain clean and coherent, with no evidence of metal collapse or “crève.” The tonal saturation is therefore achieved through disciplined additive construction rather than through destructive or accidental processes, fully consistent with Van Dyck’s controlled and methodical working technique.

High-magnification macro view showing a transition zone in which form is constructed through tightly grouped bundles of curved, parallel etched lines that progressively increase in density and are integrated into adjacent cross-hatched tonal fields. The curvature and spacing of the lines follow the underlying anatomy, producing a smooth volumetric gradient rather than a flat tonal field. Each stroke remains individually legible, with ink seated inside the incised channels and the surrounding paper showing localized compression from printing pressure. The tonal modulation is therefore achieved by controlled variation in line density, direction, and curvature, fully consistent with Van Dyck’s disciplined and highly structured intaglio technique.

High-magnification macro view showing the three-dimensional relief of the engraved lines. The edges of the strokes remain physically active, with ink seated inside the grooves and a clearly perceptible micro-relief rising above the surrounding paper surface. The lines are not flat or planar: they retain volume, edge definition, and directional structure produced by the incised copper plate and transferred under pressure to the damp paper. This preserved line-edge relief is a physical characteristic of true intaglio printing and cannot be produced by surface or photomechanical processes. The continuity and sharpness of the grooves also indicate minimal plate wear and an early or well-preserved phase of the plate’s working life.

High-magnification macro view showing ink seated inside the incised channels together with clear lateral compression and flattening of the paper fibers along the edges of the printed lines (“fiber squash”). The paper surface is plastically deformed where the damp sheet was forced into the grooves of the metal plate under the pressure of the press. The boundary between inked line and unprinted paper remains sharply defined, and the fiber structure shows directional displacement away from the groove. This combination of ink-in-groove, edge relief, and fiber compression constitutes direct physical evidence of true intaglio printing and cannot be produced by surface, Plano graphic, or photomechanical processes.

MICROSCOPIC ANALYSIS

Microscopic examination of the print was conducted in order to characterize the physical behavior of the ink, its interaction with the paper fibers, and the structural mechanism by which the tonal range of the image is constructed. This level of observation allows direct distinction between genuine intaglio printing and any form of photomechanical or surface-based reproduction.

At high magnification, the ink does not appear as a continuous surface layer. Instead, it is consistently observed to be integrated within the fiber network of the paper, following the micro-topography of the sheet. No evidence of polymeric film, gelatin sizing, modern coating, or surface sealing layer is present. The ink penetrates the paper structure in a manner consistent with traditional oil-based intaglio inks printed on rag paper.

The full tonal range of the image — from the lightest passages of facial modelling to the densest black areas — is constructed exclusively by graphic means: variation in line density, cross-hatching frequency, and local ink load within the engraved or etched grooves. No areas show behavior compatible with wash, surface tone, or planar ink deposition.

In the darkest passages, the black tone is revealed to be a structural black, formed by extreme accumulation of lines and cross-hatched networks rather than by a continuous ink layer. Even in these saturated zones, the individual line structure remains optically and physically legible, and the paper surface continues to govern the micro-relief of the ink deposit.

In the light tonal passages, modelling is achieved through sparse micro-lines and point work, allowing the paper to dominate the optical field. The ink remains discontinuous, and the tone emerges purely from the distribution of graphic elements rather than from any form of surface coating or tonal wash.

Throughout all observed zones, the physical behavior of the ink is internally coherent: it is consistently absorbed into the fiber network, shows no evidence of modern binders or synthetic films, and preserves the granular, slightly irregular edge morphology characteristic of hand-worked intaglio plates.

The microscopic evidence therefore confirms:

- The purely graphic construction of the tonal system.

- The absence of any photomechanical or planar printing process.

- The material coherence between ink, paper, and printing pressure.

- The authentic physical behavior of a traditional intaglio impression.

Taken together, these observations establish that the image is the result of a hand-worked intaglio process executed with full control of line, tone, and material, and not the product of any later reproductive or surface-based technique.

Microscopy shows the ink embedded within the open fiber network of the paper, with no continuous surface film or gelatin sizing layer present. This confirms the absence of modern coatings and is consistent with early handmade rag paper.

Microscopy reveals genuine incised line geometry with ink concentrated in the groove and progressively diffusing into the surrounding fiber structure. The irregular, living edges and absence of mechanical dot patterns confirm an intaglio process and exclude any photomechanical reproduction.

Microscopic view of maximum black density zone. The dark tone is produced by extreme accumulation of incised lines and cross-hatching, not by a continuous ink layer. Ink remains integrated within the fiber network and follows the paper topography, with no evidence of surface coating, gelatin sizing, or polymeric film.

Microscopic view of a light tonal zone in the facial modelling. The tone is constructed exclusively through sparse micro-lines and point work, allowing the paper to dominate the optical field. No continuous ink layer is present.

DIGITAL OVERLAY AND COMPARISON WITH INSTITUTIONAL REFERENCE

A direct digital overlay was performed between the Álvarez Collection impression and the institutional reference preserved at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-OB-11.896). The comparison was carried out using uniform proportional scaling and alignment based on stable structural axes of the image (eyes, nose, head contour, and overall plate outline). No deformations, optical warping, or interpretive adjustments were applied.

Despite differences in inking density, surface tone, and overall printing appearance, the overlay demonstrates an exact structural correspondence between both impressions. The contours of the head, the facial features, and the position of the eyes, nose, mouth, and the internal proportional relationships coincide precisely.

This structural identity confirms that both impressions derive from the same copper plate. The observable differences are limited to variables inherent to the printing process (inking, pressure, and wiping) and to the later history of each individual sheet, and do not affect the underlying geometry of the matrix.

The overlay therefore constitutes direct material evidence of matrix identity between the present impression and the Rijksmuseum example, independent of condition, inking quality, or surface appearance.

Structural overlay comparison. Green: Álvarez Collection impression. Black: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-OB-11.896). Although the images differ in scale, orientation, and photographic conditions, the complete alignment of the plate outline and internal construction lines confirms that both impressions originate from the same copper matrix.

Facial area — matrix correspondence. Green layer: Álvarez Collection impression. Black layer: Rijksmuseum (RP-P-OB-11.896). The coincidence of every anatomical contour and internal modelling stroke demonstrates that this highly sensitive area was printed from the same engraved plate, independent of differences in inking or surface condition.

Ruff and collar — structural concordance. Green: Álvarez Collection impression. Black: Rijksmuseum (RP-P-OB-11.896). Despite variations in printing appearance and image registration, the exact match of the line architecture and proportional relationships proves a common origin in the same copper plate.

Provenance and History

The print was transmitted from generation to generation, remaining within the same family. Its state of preservation suggests minimal historical handling: it was stored for decades in a protected environment, away from direct light and damaging humidity fluctuations. It is likely that the print has been handled far less during the past one hundred years than during the recent technical examination conducted under microscopy, raking light, and transmitted-light watermark analysis.

This continuity of private custody—without recorded sales, auction appearances, or dealer interventions—helps explain the exceptional condition of the sheet and the survival of fragile physical features often lost in circulating impressions, including residual micro-relief, intact margins, and a fully preserved watermark.

Provenance therefore supports attribution not only through lineage, but through material coherence: every aspect of the sheet’s condition aligns with an impression that has remained intact and undisturbed since the seventeenth century.

References

Portret van Jans de Wael — Rijksmuseum — RP-P-OB-11.896

New Hollstein Dutch 15-2(6)

Mauquoy-Hendricx (van Dyck) 17-2(6)

Rembrandt WIRE Project (Cornell University). Ongoing digital watermark imaging and census research.

Referenced here for comparative framework on watermark documentation practices (methodological context).

Access and research collaboration

High-resolution files, complete macro-photography sets, and the internal technical dossier for the Álvarez impression of Jan de Wael are available to researchers upon request. Comparative video-microscopy sessions can also be arranged for institutions interested in examining in detail the physical features associated with early phases of plate use.

All observations presented on this page are based on direct examination of the private impression and on published images from institutional collections. Attribution, dating, and official terminology remain open to academic discussion and are offered here as a contribution to ongoing research on Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) prints.

For inquiries, image permissions, or collaborative research projects, please use the contact form on the main website or write to:

susana123.sd@gmail.com

fineartoldmasters9919@gmail.com

susana@alvarezart.info

Phone: +1 786 554 2925 / +1 305 690 2148

Álvarez Collection Verification Record #AC-VD-243-REV-2026