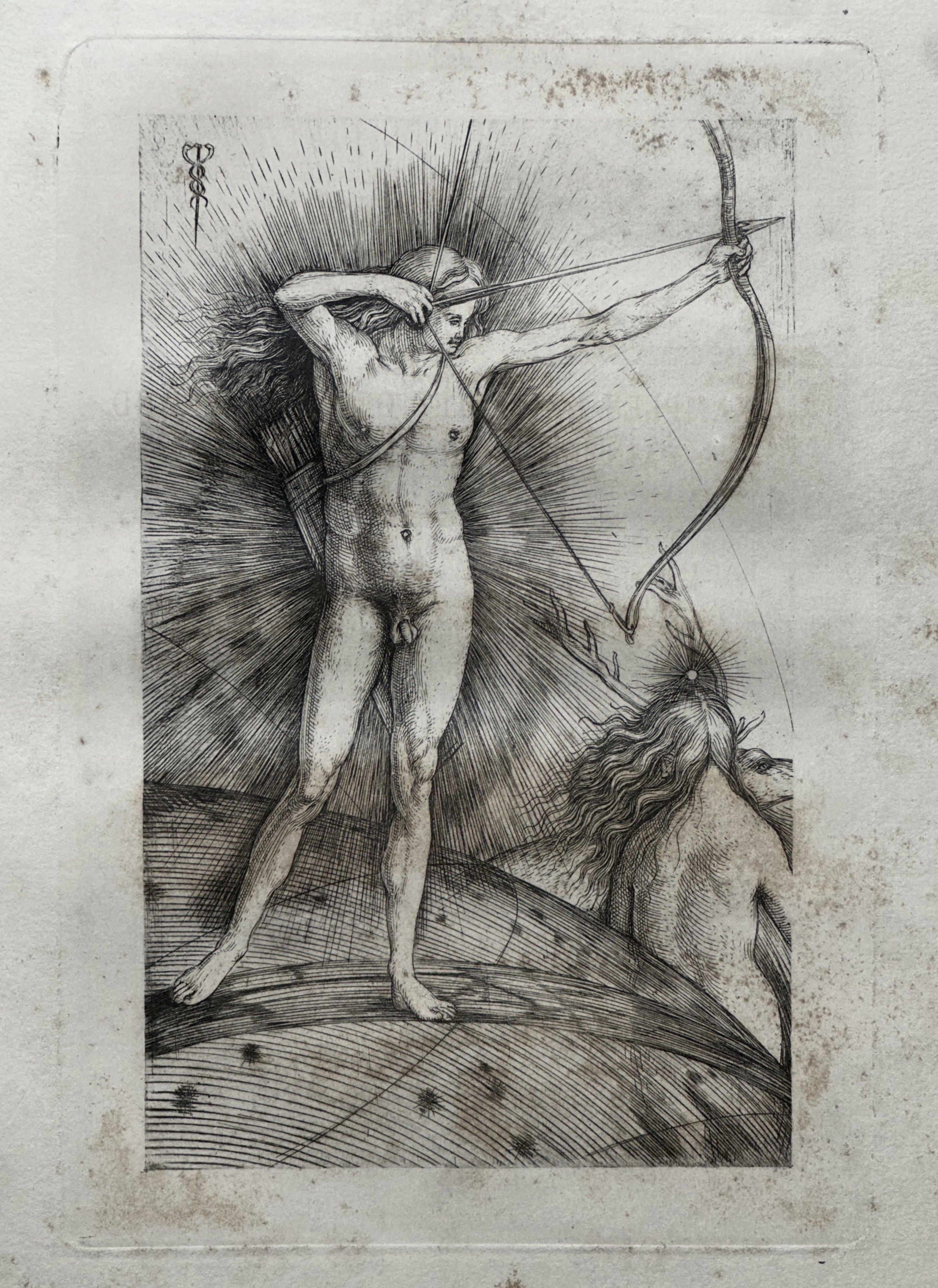

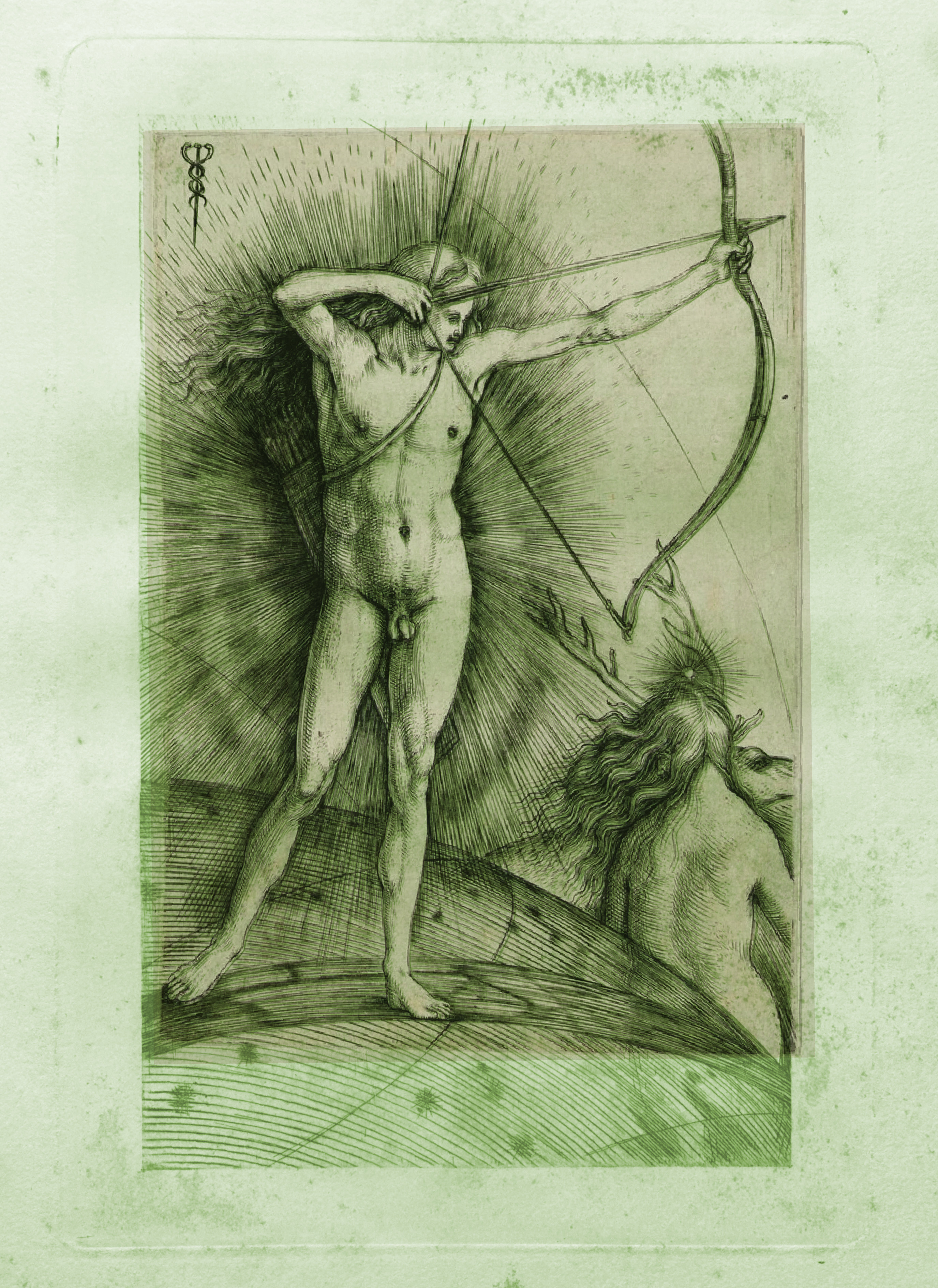

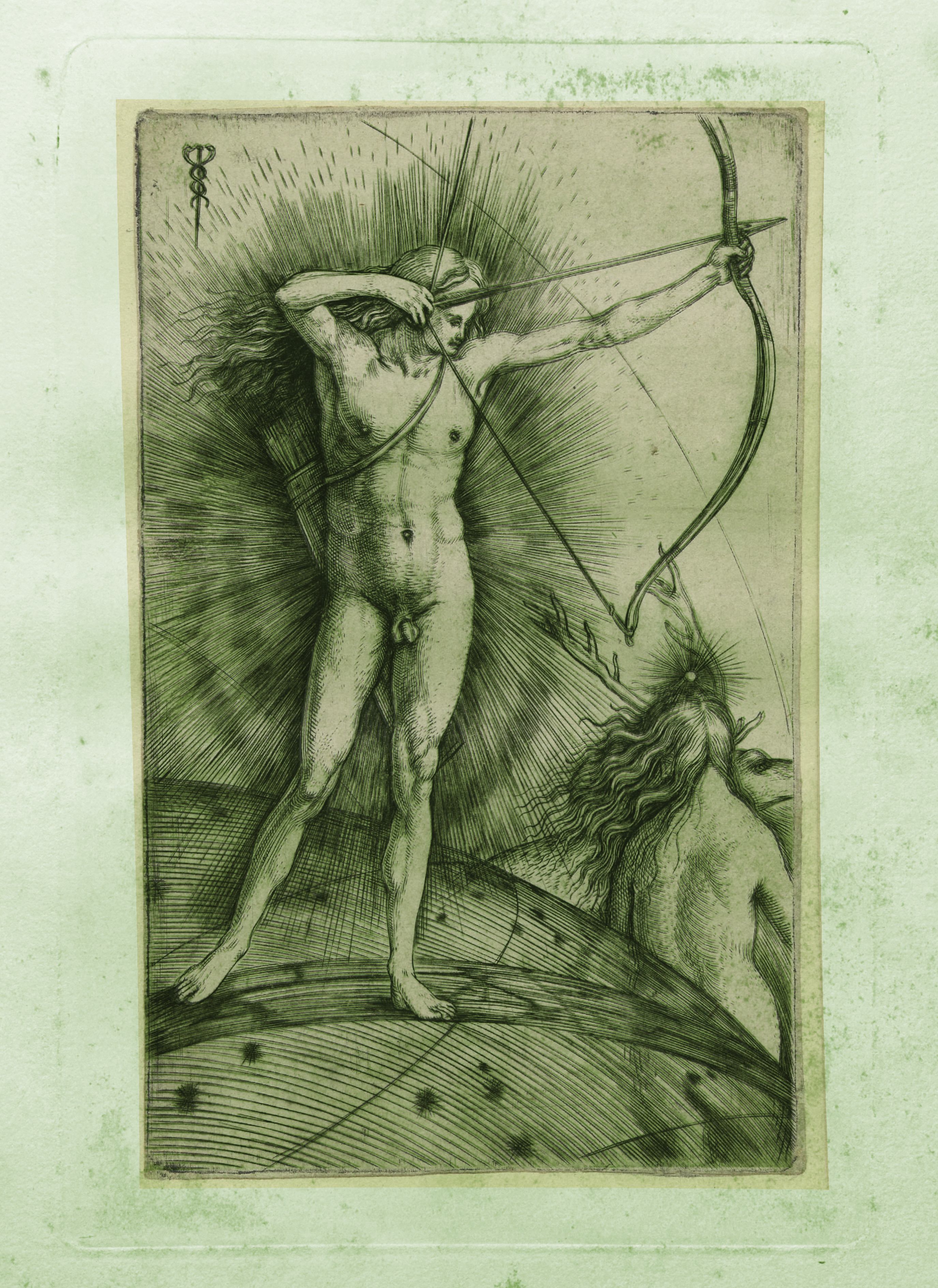

Apollo and Diana — Jacopo de’ Barbari

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay.

TECHNICAL DATA

- File ID

- AC-JB-244-REV-2026

- Artist

- Jacopo de’ Barbari (c. 1460/70 – before 1516)

- Title

- Apollo and Diana

- Date of Execution

- C.1503–1505

- Technique / Materiality

- Engraving.

- Dimensions

- Height 161 mm × Width 102 mm

- Sheet Dimensions

- Height 320 mm x Width 245 mm

- Sheet Weight

- 15 grams

- Collection

- The Álvarez Collection (Miami)

- Provenance

- Private family collection, preserved over generations

Research Objective

Technical documentation of the print through direct material observation, including paper structure (laid pattern and chain lines), ink–fiber interaction, plate mark under raking light, line morphology under macro/microscopy, and tonal mechanism analysis (dense hatching, selective burr). Comparative overlay.

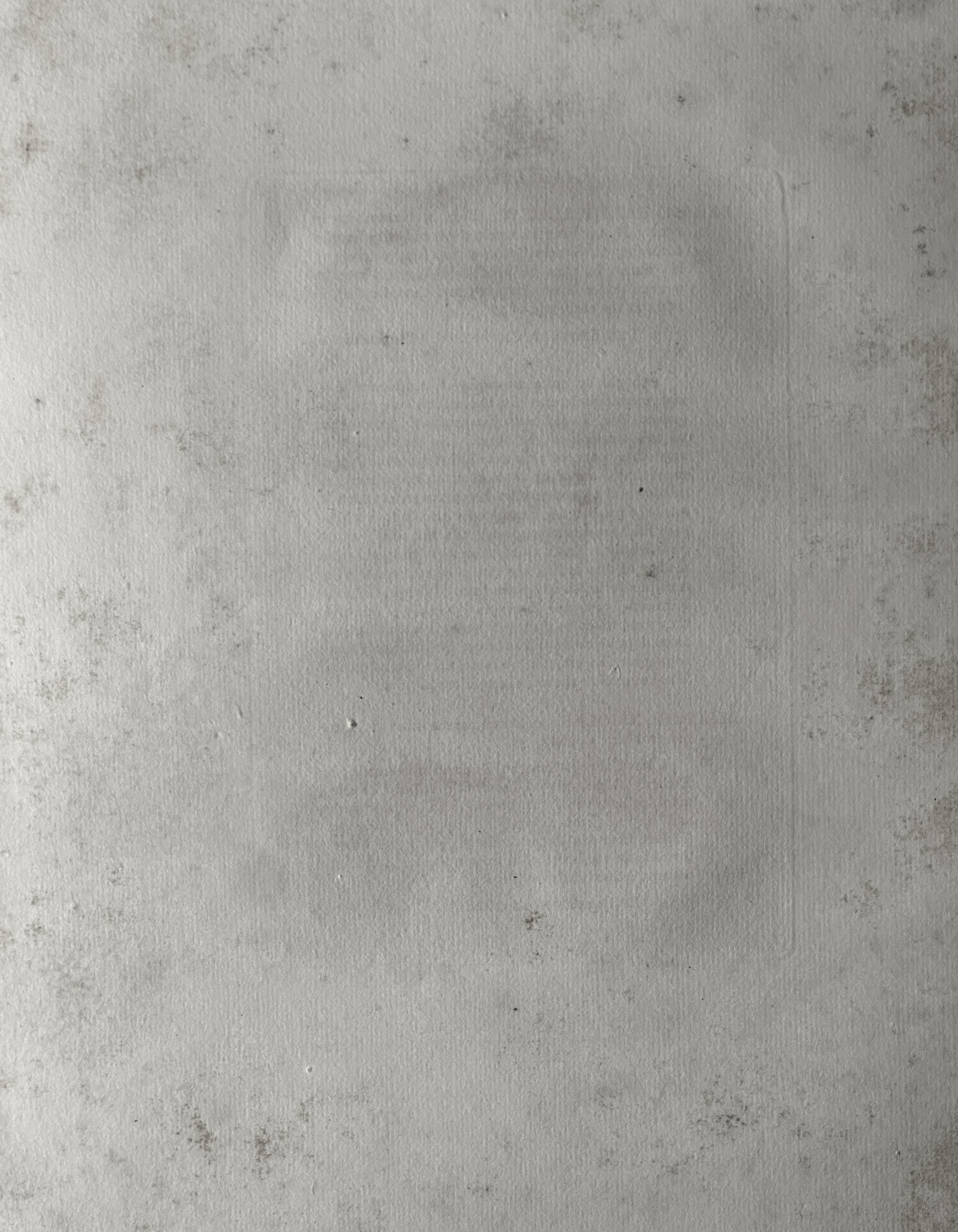

PAPER ANALYSIS

Support, Fiber Structure, Chain Lines, and Ink Interaction

Structure of the paper support

The print is executed on a laid rag paper produced by hand mould. Under transmitted light and microscopic examination, the characteristic structure of laid paper is clearly visible, with a regular system of fine laid lines and a secondary system of more widely spaced chain lines.

The sheet is notably thick and rigid in handling, closer in body to light card stock than to a thin printing paper. With a total sheet weight of approximately 15 grams and dimensions of 32 × 24.5 cm, the calculated paper density is approximately 190 g/m², placing it in the upper range of early modern handmade rag papers used for intaglio printing.

This substantial thickness and mass are consistent with high-quality rag paper intended to withstand the pressure of the intaglio press, allowing deep penetration of ink into the fiber network without surface disruption. The physical stiffness, fiber cohesion, and resistance of the sheet are fully coherent with historical hand-moulded laid paper and incompatible with lightweight or industrially produced supports.

Chain line system: 25 mm and 27 mm spacing

Measurement of the chain lines reveals two recurring spacings:

- In some areas, 25 mm between chain lines

- In other areas, 27 mm between chain lines

This variation is fully consistent with handmade laid paper, where slight shifts in mould tension and positioning produce non-uniform but structurally coherent spacing.

Such values fall squarely within the expected range for early modern European rag papers used for intaglio printing.

Fiber structure and paper texture

Microscopic images of the paper surface reveal:

- A dense network of long, irregular rag fibers

- Natural interlacing and random orientation of fibers

- No evidence of industrial pulp, short-cut fibers, or machine homogenization

The surface texture shows:

- A micro-relief consistent with pressed rag paper

- Slight irregularities and natural compression zones caused by the printing pressure

- No coating layer, no gelatin film, and no artificial surface treatment

This is the behavior of a true historical rag paper.

Ink–paper interaction

Microscopic examination shows that the ink does not sit on the surface as a flat or continuous layer. Instead:

- The ink is embedded inside the fiber network

- It occupies both the engraved grooves and the interstices between fibers

- The edges of the lines show capillary diffusion into the surrounding paper

- In lighter areas, the fibers remain visibly clean and structurally intact

This penetration pattern is characteristic of intaglio printing under pressure.

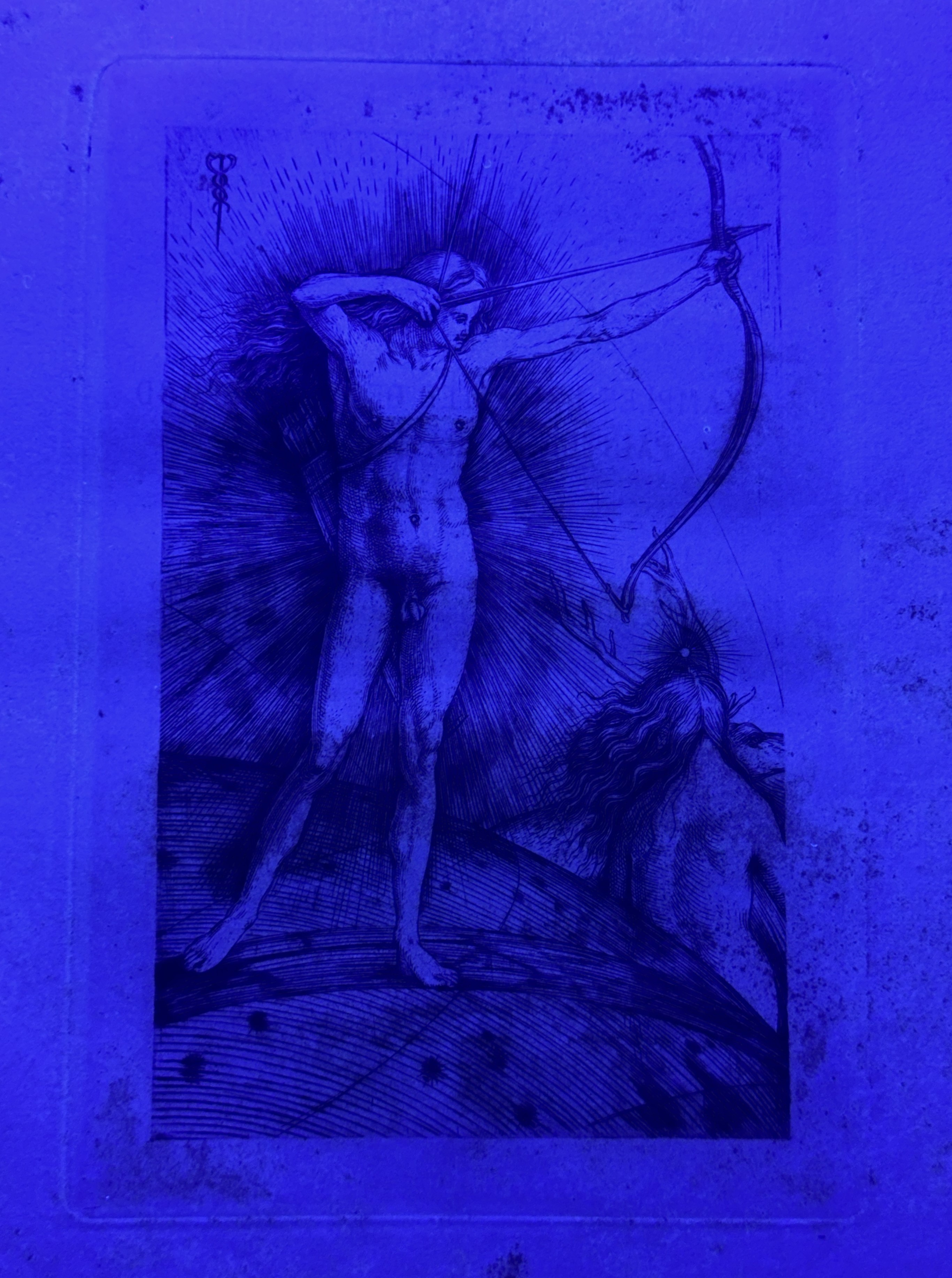

Behavior under ultraviolet light

Under ultraviolet illumination, the paper shows:

- No uniform modern fluorescence associated with optical brighteners or modern treatments

- A natural, irregular response consistent with aged rag paper

- No evidence of modern coatings, fillers, or surface sizing layers

The inked areas behave differently from the bare paper, confirming that the ink is physically embedded within the paper structure rather than forming a superficial film.

Technical conclusion on the paper

The combined evidence of laid paper structure, chain line spacing at 25 mm and 27 mm, rag fiber morphology, ink penetration into the fiber network, and natural ultraviolet response demonstrates that the support is a genuine handmade laid rag paper consistent with early intaglio printing.

CONSTRUCTION BY MICRO-LINE FIELDS

In Apollo and Diana the image is not built from tonal masses or flat areas, but through the systematic accumulation of extremely fine lines incised into the plate. The modeling of forms, spatial depth, and tonal transitions is achieved exclusively through variations in density, orientation, and superposition of fields of micro-lines.

There is no true “continuous tone” anywhere in the print: every shadow, volume, or gradation is an optical result of the concentration or dispersion of individual strokes. On a material level, each of these lines corresponds to a physical groove incised into the metal and transferred to the paper under pressure.

This system of construction by line fields is characteristic of high-precision burin engraving and demonstrates an extreme level of control over both tool and support, reaching line resolutions on the order of a few hundredths of a millimeter.

MACROGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

Structural analysis of form, volume, and light by engraved stroke systems

The following six macros document the fundamental constructive principle of the image: form, volume, depth, and light are not produced by tonal washes, continuous surfaces, or masses of ink, but exclusively through organized systems of incised micro-lines.

Every visible element—faces, bodies, hair, animals, background, and transitions between planes—is built through the orientation, curvature, superposition, and progressive densification of individual strokes physically engraved into the plate. Each line corresponds to a real groove holding ink in relief.

These images demonstrate that the work operates as a fully linear, fully intaglio system: light, shadow, and volume emerge solely from the architecture of lines, not from tone. The six macros below analyze this principle across different zones of the composition: facial definition, radiant background, anatomical modeling, hair and animal forms, plane transitions, and crossing line fields.

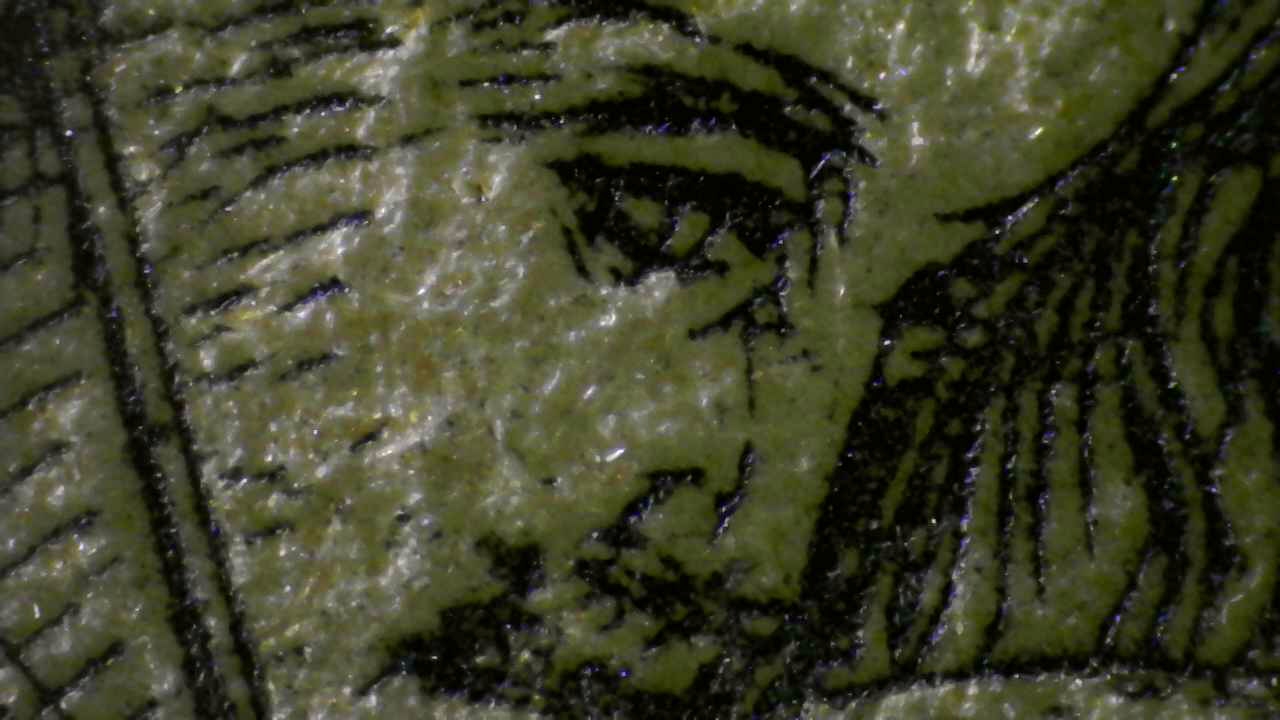

Macro of the face showing eye definition through stroke hierarchy: the upper eyelid is reinforced with greater pressure to create depth, while iris/pupil and the lower lid are suggested with minimal marks and reserved paper highlights. Facial volume is built through short, directional micro-hatching rather than continuous tone, demonstrating extreme manual control.

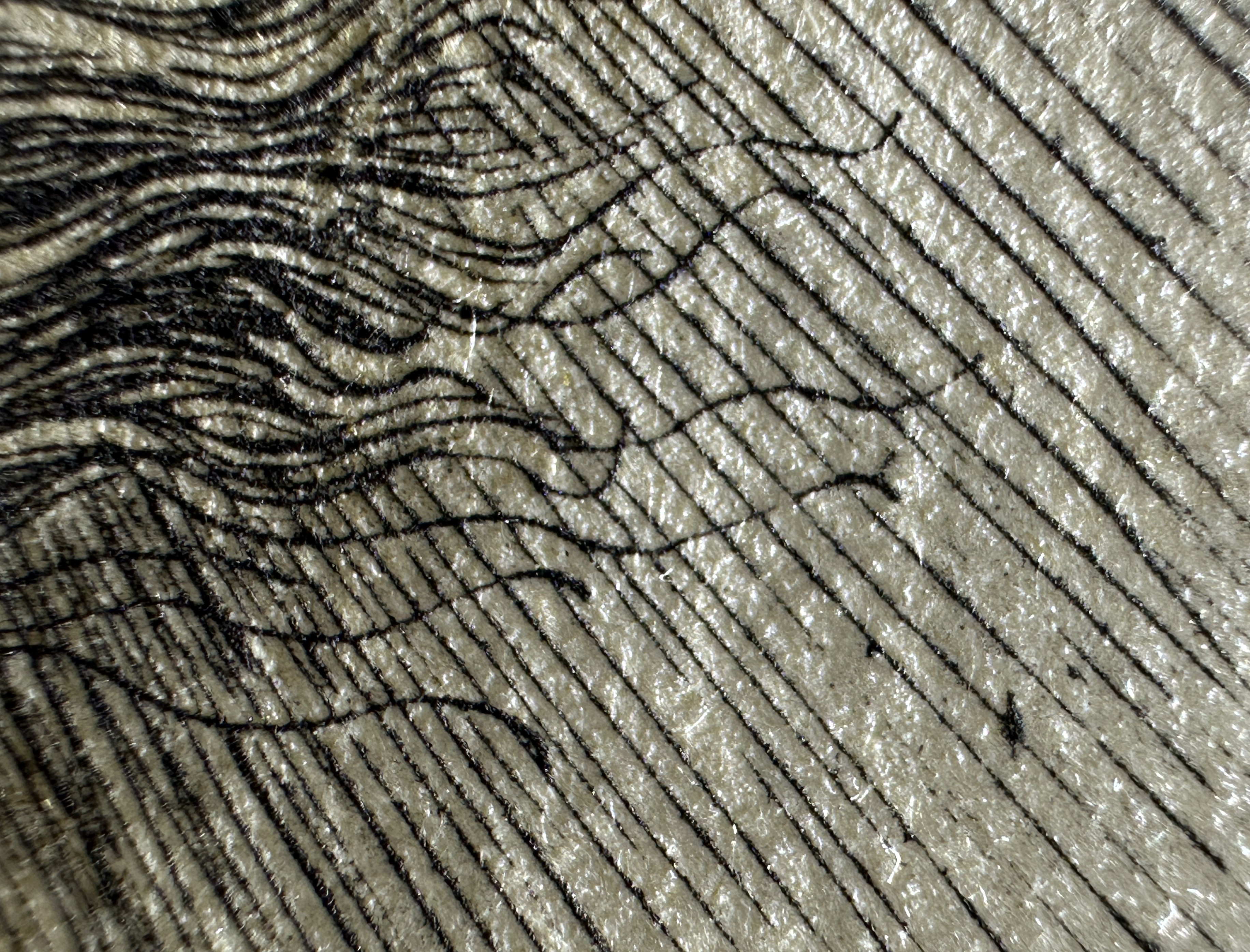

Macro of the radiant background showing a continuous field of incised micro-lines organized in directional systems that cross and curve to generate the sensation of radiating light and spatial depth. There is no continuous tone: the entire appearance of light and gradation is produced exclusively through variations in density, orientation, and superposition of individual lines. Each stroke corresponds to a physical groove with ink seated in the furrow and visible relief, confirming a purely intaglio construction by direct incision into metal.

Macro of the body showing anatomical construction through the superposition of incised micro-line fields in different directions. Volume is not obtained through outlines or tonal fills, but through the crossing, curvature, and progressive densification of strokes that follow the topography of the form. Even in the areas of highest density, each element remains an individual line with physical relief and ink seated in the furrow.

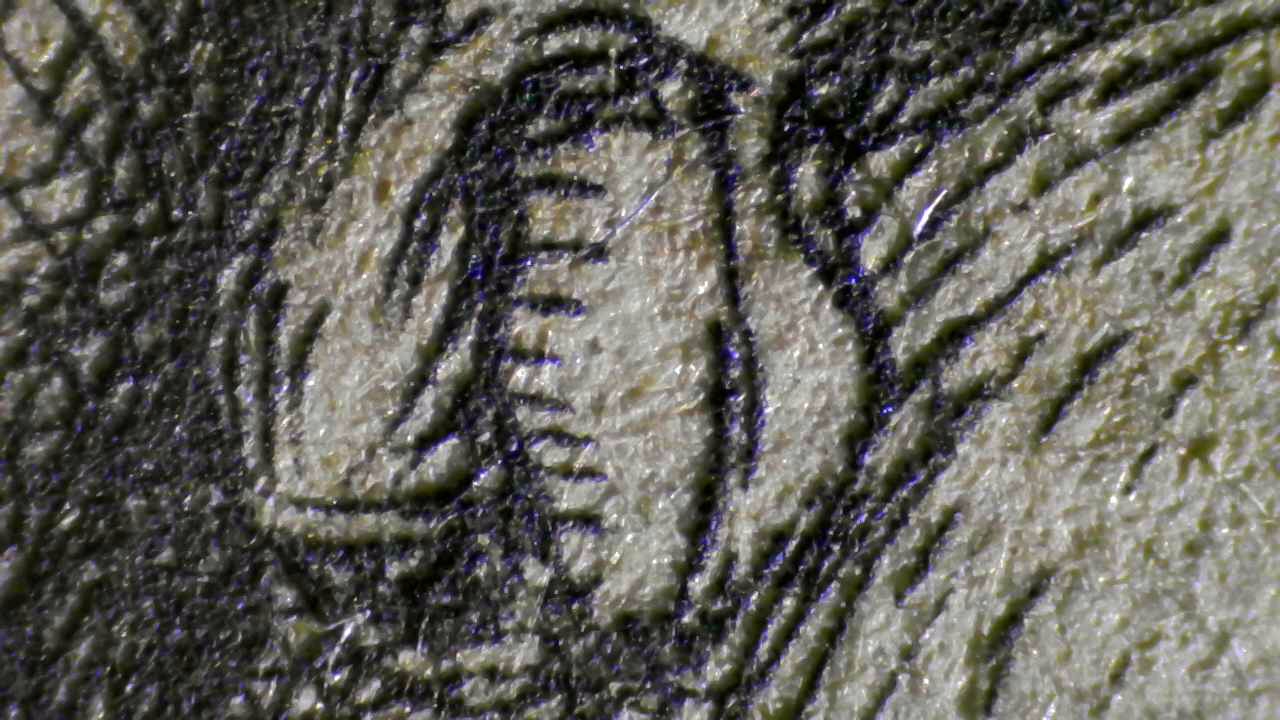

Macro showing Diana from behind, with her hair constructed through fields of undulating micro-lines, alongside the stag’s head, where the eye and anatomy are likewise defined by the accumulation of individual strokes. There are no continuous surfaces or tonal masses: both the hair and the animal’s form exist solely through the orientation, curvature, and variable density of incised lines.

Macro of Diana’s back where bodily volume is not constructed through tonal masses, but exclusively through dense fields of incised micro-lines. The curvature of the torso emerges from the progressive variation in stroke direction, length, and density. Each line corresponds to a physical groove retaining ink in relief, with slight capillary diffusion into the rag paper.

This macro shows fields of incised micro-lines with crossing hatch systems and physical relief, accompanied by microscopic capillary diffusion of the ink and traces of residual micro-plate tone. The “spray” of black dots is an organic phenomenon resulting from the ink–paper interaction in an old rag paper.

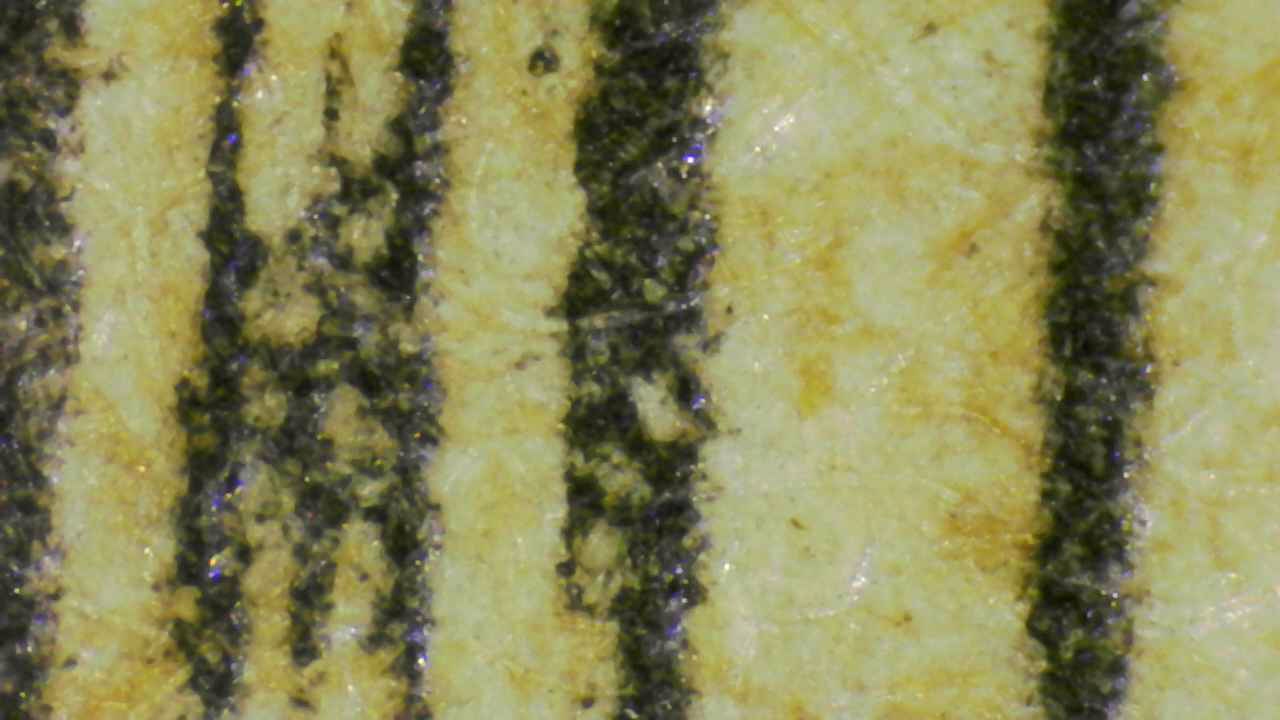

Construction by micro-lines

Measurement, density, and modulation of the engraved stroke. This subsection focuses on the stroke itself as the fundamental constructive unit of the image. While the previous macros demonstrated how entire forms and fields are built through micro-lines, the following figures document the internal mechanics of that system: line density per millimeter, transitions between planes, the superposition of different drawing logics, and the generation of darker values through pure line compression. These images show that each visible mark is an independent physical groove engraved into the plate and filled with ink, and that all tonal, spatial, and volumetric effects emerge exclusively from the organization, spacing, and density of lines—without any use of tonal masses, continuous surfaces, or mechanical screening.

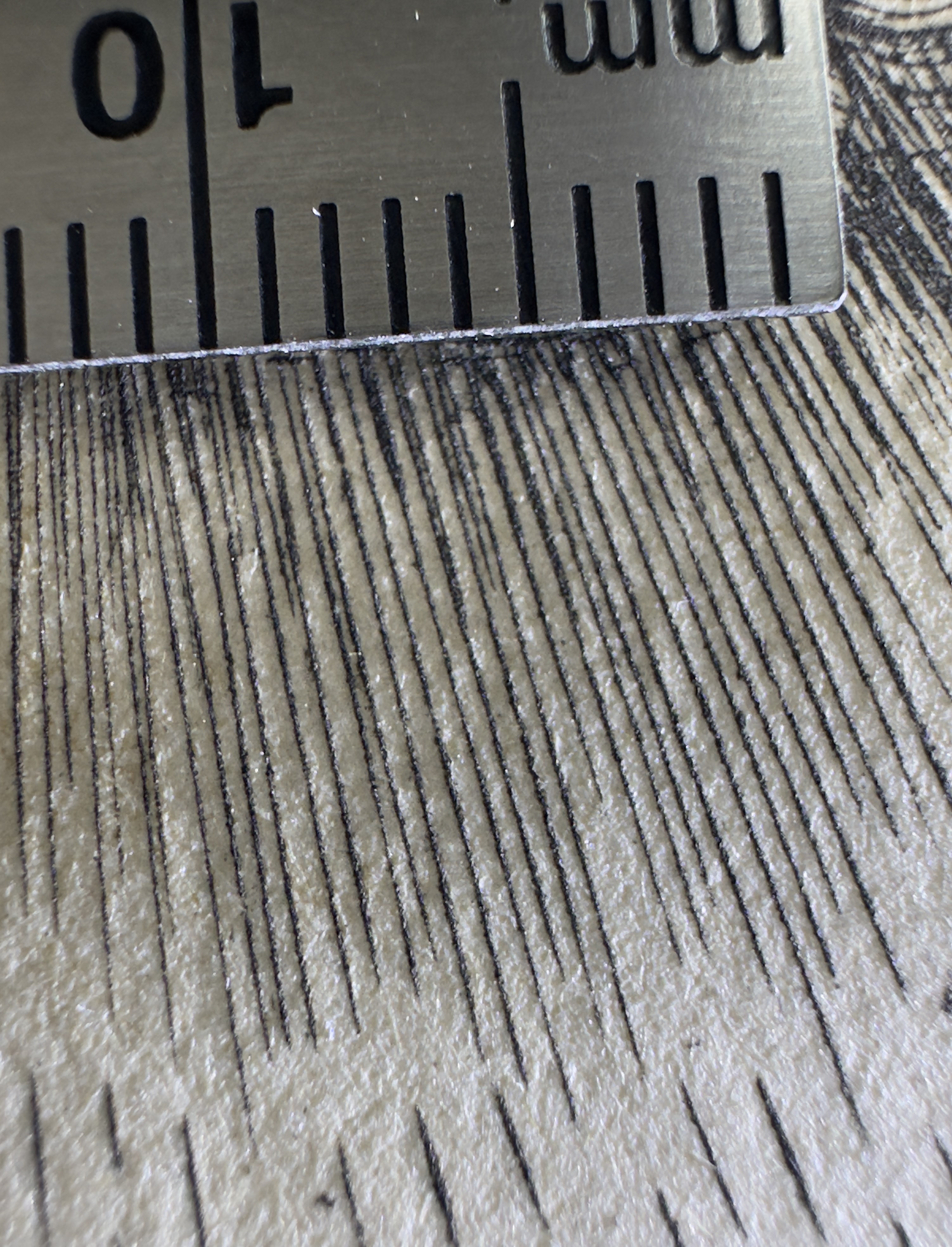

Calibrated macro with millimeter ruler showing a field of extremely dense incised lines. Within a one-millimeter segment, approximately 12 individual strokes are visible, each corresponding to a separate physical groove retaining ink. The regularity, continuity, and organic spacing between strokes confirm a purely linear construction system.

Macro showing the transition between different planes of the body and background through changes in orientation, density, and spacing of incised micro-line fields. Volume is not constructed through tonal masses but through the progressive modulation of parallel and crossed lines.

Macro showing the coexistence and superimposition of two different drawing systems: a field of straight, parallel, regularly spaced lines forming the structural volume, and a set of flowing, curved lines describing the movement of the hair. Both types of lines are physically incised into the plate and hold ink in relief.

Macro showing how the artist progressively increases the density of micro-line fields to produce visually darker areas, without resorting to ink masses or continuous surfaces. Tone emerges exclusively through compression, superposition, and variation in the orientation of incised lines.

MICROSCOPIC ANALYSIS

Microscopic structure of the printed line — physical evidence of intaglio printing: ink embedded in fibers, continuous grooves, and capillary diffusion in rag paper. The following microscopic images examine the print at the level where the physical nature of the process becomes unmistakable. At this scale, the image is no longer a “drawing” or a “reproduction,” but a material object composed of paper fibers, ink, and pressure.

Across all examples, the same fundamental phenomena are observed: the ink is not resting on the surface, but is embedded between and around the paper fibers, following the microscopic relief left by the metal plate. Each black line corresponds to a real physical groove cut into the plate, now visible as a continuous channel filled with ink and partially surrounded by fibers compressed during printing.

In many areas, a slight capillary diffusion of the ink into the rag paper can be seen, producing soft, organic micro-spreading at the edges of the lines. This is a natural consequence of dampened handmade paper under pressure and is incompatible with any photomechanical or surface-based printing process.

The microscope thus confirms, at the material level, what is already evident in the macros: this is not a heliogravure, not a photogravure, not a facsimile, and not a surface print, but a genuine, mechanically printed intaglio impression from an engraved plate.

DIGITAL OVERLAY AND COMPARISON WITH INSTITUTIONAL REFERENCE

The following comparative overlays confront the Álvarez Collection impression with two independent institutional reference impressions preserved at the Louvre and the British Museum.

These comparisons are not based on visual resemblance or stylistic judgment, but on strict geometric and structural coincidence: the full architecture of the engraved composition — including figure proportions, line trajectories, curvature of the bow, radiation field, ground construction, and secondary elements — aligns with no measurable deviation beyond minor paper deformation and printing variability.

Such a degree of correspondence is only possible when the impressions originate from the same engraved copper plate. No copy, reinterpretation, or photomechanical process can reproduce this level of point-to-point structural identity across the entire image.

The overlays therefore demonstrate, in purely material and geometric terms, that the Álvarez Collection impression belongs to the same physical matrix as the institutional impressions. This establishes plate identity independently of provenance narratives, stylistic attribution, or catalog traditions.

What is shown here is not an argument of authority, but a direct material proof of shared origin.

Álvarez Collection (green) vs Louvre (black)

Overlay comparison: Álvarez Collection (green) vs British Museum (black)

Provenance and History

The print was transmitted from generation to generation, remaining within the same family. Its state of preservation suggests minimal historical handling: it was stored for decades in a protected environment, away from direct light and damaging humidity fluctuations. It is likely that the print has been handled far less during the past one hundred years than during the recent technical examination conducted under microscopy, raking light, and transmitted-light watermark analysis.

This continuity of private custody—without recorded sales, auction appearances, or dealer interventions—helps explain the exceptional condition of the sheet and the survival of fragile physical features often lost in circulating impressions, including residual micro-relief, intact margins, and a fully preserved plate impression.

Provenance therefore supports attribution not only through lineage, but through material coherence: every aspect of the sheet’s condition aligns with an impression that has remained intact and undisturbed over time.

Access and Research Collaboration

High-resolution files, complete sets of macrophotographs, and the internal technical dossier of Álvarez's print of Apollo and Diana are available to researchers upon request. Comparative video microscopy sessions can also be arranged for institutions interested in examining in detail the physical characteristics associated with early stages of the plate's use, in support of scholarly evaluation and curatorial review.

All observations presented on this page are based on direct examination of the private print and published images from institutional collections. Attribution, dating, and official terminology are subject to scholarly debate and are offered here as a contribution to ongoing research on the engravings of Jacopo de’ Barbari (c. 1460/70 – before 1516).

For inquiries, image permissions, or collaborative research projects, please use the contact form on the main website or write to:

susana123.sd@gmail.com

fineartoldmasters9919@gmail.com

susana@alvarezart.info

Phone: +1 786 554 2925 / +1 305 690 2148

Álvarez Collection Verification Record #AC-JB-244-REV-2026